On the spectrum, on the job

Keeping workers with autism safe

People with autism spectrum disorder – commonly referred to as individuals “on the spectrum” – exhibit a wide range of symptoms and varying levels of intellectual disability.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines ASD as “a developmental disability that can cause significant social, communication and behavioral challenges.” Some people on the spectrum may exhibit gifted learning, as well as cognitive and problem-solving abilities, CDC states. Others may require assistance in daily life, while some may fall somewhere in between.

A 2014 Gallup poll commissioned by Special Olympics and conducted by the University of Massachusetts at Boston concluded that 34 percent of Americans with intellectual disabilities are in the workforce. Among them, 53 percent are “competitively employed” at market-driven wages alongside workers without cognitive differences, 38 percent are employed in work centers designed for individuals with intellectual disabilities and 9 percent are employed in other settings, including self-employment.

Experts note that employers must be sensitive to individuals’ needs when working to safely integrate individuals with autism and other neurosensitivites into the workforce.

Safety+Health explores the multifaceted issue of autism and worker safety with several experts who employ or assist individuals with autism.

‘You’re looking at a wide spectrum’

Other Gallup poll results found that, among people with intellectual disabilities who were “competitively employed,” 28 percent work in customer service, 22 percent work in “other sectors” such as child care and landscaping, 17 percent work in retail, 16 percent work in food service, 9 percent work in offices, and 8 percent work in manufacturing.

Temple Grandin, autism advocate and professor of animal sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO (Note: Grandin is on the spectrum): “With autism, you’re going from NASA space scientists to someone who can’t dress themselves. So, you’re looking at a wide spectrum. That’s the thing that a lot of people don’t realize.”

Leslie Long, vice president of adult services, Autism Speaks, New York: “Because the spectrum is so broad, a person with autism may be looking for an entry-level position or have a master’s degree and be looking for a management-level position. What has been a constant challenge is the traditional interview process. Assessing a person with autism … in a traditional, face-to-face interview is simply not a good way to assess his or her true abilities. Giving him or her a sample job task or a trial work period is a much more effective strategy for both parties.”

Michael Fieldhouse, director of emerging businesses and cyber security and developer of the Dandelion Program for persons with autism, DXC Technology, Canberra, Australia: “[The program is] not focused on just having jobs. You have to look at this as, can you give an individual on the spectrum a career in your workplace? … When you’re building careers, you’re actually then allowing them to find what skills to have, that drive, and have a working life, not just have a job for a period of time. That’s the critical thing. It’s a different ideology in regards to, ‘Get a job,’ [versus], ‘Here, we’ll try and build a career for you.’”

Valerie Paradiz, founder and director, Neuroscape Navigators, Boulder, CO(Note: Paradiz is on the spectrum): “If you’re not on the spectrum and you work with someone on the spectrum, you’re definitely going to see differences in social communication, no matter where they’re at on the spectrum. … You’re also very likely going to see sensory differences, and in different ways. They will be reacting to the environments they’re in in different ways. So, you might see anything from someone hand clapping to someone suddenly just getting up and walking out of a room without saying, ‘I have to go.’ And those could both be for sensory reasons.”

Keeping workers safe

Integrating people on the spectrum into the workforce begins with effective safety training. Experts remind employers that there’s no one-size-fits-all training strategy for workers with cognitive differences – learning styles and speeds vary by individual. Workers with autism may require accommodations to help them perform their jobs. Panelists for this article, however, stress that these accommodations are often inexpensive – some as basic as allowing an employee to listen to music on a portable device to help curb distractions from outside noise.

Abbie Wells-Herzog, autism specialist in vocational rehabilitation services, Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development, St. Paul, MN: “Every person on the autism spectrum is different, so they’re going to have different knowledge and different levels of safety. I think when we look at employers keeping folks safe, I would hope it’s not only employers … but also the people who help people get jobs. I would hope if someone has some judgment issues or has some issues in knowing if something is safe or is not safe, that there would be some guidance in that. … I think so many of our students and adults (on the spectrum) have been focused on all the things they can’t do for a long time that they’re naturally kind of safety-conscious. … There’s so much focus, and it shouldn’t be this way … but it’s really focused a lot on what you can’t do, and so I think it develops a heightened awareness of the things that are not safe for you, in a way. But then there’s always going to be people that don’t know.”

Grandin: “[People with autism] can be extremely safe workers. They like to obey rules. You tell them what the rules are, they obey them. If you have to wear fall protection, they wear it. And then they’ll get after someone who doesn’t do it.”

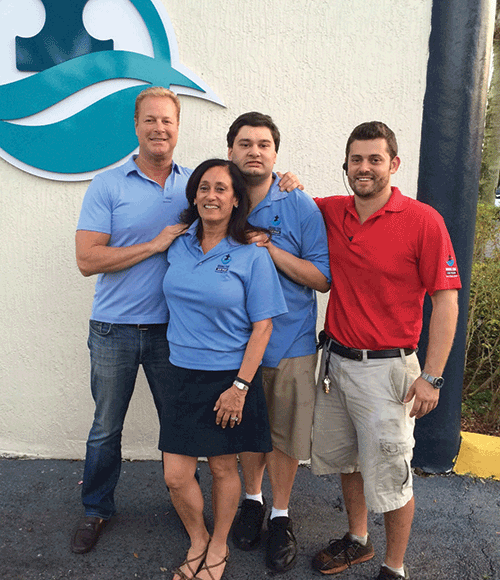

Tom D’Eri, co-founder and chief operating officer, Rising Tide Car Wash, Parkland, FL(Note: Rising Tide has employed 92 associates with autism at its two South Florida car washes): “It’s not like we have any special safety standards here that every car wash doesn’t try to operate. ‘Don’t step on the conveyor. You have to step over it, in case you get your shoelaces caught. Don’t pull out any hoses until the equipment is locked out.’ … They don’t do that. You couldn’t pay them enough money to step on the conveyor.”

Janine Bain, director of corporate risk and compliance, Goodwill Industries-Suncoast Inc., St. Petersburg, FL: “We have employed a variety of people on the spectrum, but depending on where they are on the spectrum dictated whether or not they were successful with us long-term because they’re all different. … We had a person who was magnificent who … managed a staff of about 35 people. It was a logistics position, so they were arranging transport of product, so you’re talking about transporting, warehousing, storage, inventory, everything that goes with transportation. … We have one person who operates a forklift and has been doing so in excess of 20 years. And in that time, there have been incidents – most of which have been preventable – but my standard employees have an equal, if not higher, rate of those types of incidents. So, again, it’s almost irrelevant that they are on the spectrum.”

Wells-Herzog: “I think it’s fair that whoever is training you – whether you’re doing an apprenticeship or doing on-the-job training – that someone takes you aside and says, ‘You need to be focused on safety here. There’s some issues here.’ I think being straightforward is the best way.”

Paradiz: “If it’s a supervisor, or even a co-worker, providing information about doing a task or completing a deadline, one thing to do is to check that the information was processed correctly by asking them, ‘Can you reflect back to me what I just said or summarize what I just told you?’ That’s one really helpful tool.”

Grandin: “Work them into it slowly. Sometimes they’ll take longer to train, but once they’re trained, they’ll be really good. … If you take the time to train them for specialized tasks, they can be some of your best employees. They may need to be coached on some of the social stuff, but safety usually is not an issue.”

Communication

Experts advise communicating clearly and concisely with workers on the spectrum. When possible, use outlines or visual support to help convey or reinforce a message. That strategy can help employers or workers effectively engage with co-workers on the spectrum, from the interviewing process onward.

Paradiz: “So, not communicating everything verbally. Or, if it is verbal, that there’s also a written checklist or some sort of illustration or a video, you know, to support or reinforce information being conveyed. Because one of the differences of autism can be how we process language and how we also read others socially, right, and what they’re conveying. And so sometimes there can be sort of misinterpretation of information without adding those elements of visual support.”

John D’Eri, CEO and co-founder of Rising Tide Car Wash, Parkland, FL: “If you communicate properly, you get a great result. So, basically, ‘Stay within these lines.’ That’s the instruction, not, ‘Don’t stray outside these lines.’ That’s not the instruction. … Rules give you comfort. ‘I’m following the rules. I’m doing it right.’ End of discussion. ‘I’m comfortable.’ And it’s not like they’re robots or automatons. That’s not true.”

Bain: “For those on the spectrum, I have not found [training] to be any different than for my standard employees. It’s making sure there is a clear understanding of what their task is and how to do it safely, and then enforcement by repetition.”

Grandin: “If a task has more than three steps, give them a checklist. And you don’t have to write a book about it. You just have to give a keyword to trigger the memory. … And give no surprises in changing the work task. Take a little more time to help them learn a new task, and provide a checklist.”

Paradiz: “Separate the person’s ability to do the job from the person’s ability to engage in soft skills at work that aren’t necessary to the job, like watercooler talk or unstructured, sort of, light conversation. Those are the things that people with autism generally don’t do in sort of the normative way at a job, and it doesn’t mean that they can’t perform the work. … Sometimes, for those who become easily fatigued by too much social interaction, it just makes it harder for them then to perform their work well, which is what they want to do first. They want to be employed. They want to maintain employment. And so some of those other related social activities at work could be extremely depleting and a deal-breaker for some if it’s expected, even though it’s not related to performance of tasks.”

Fieldhouse: “Manager and co-worker training, that creates empathy. It creates understanding. That’s where you’re going to really get your benefit in the long term, because that way both managers and co-workers learn.”

Disclosure not required

Individuals with ASD are not legally obligated to inform a supervisor or human resources personnel. However, only by reporting a disability can workers receive the workplace accommodations to which they are entitled under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Long: “For people with autism and other non-apparent disabilities, the decision to disclose your diagnosis can be complicated. Many employees with autism fear being judged because the accommodations they need often are related to the soft skills on a jobsite and are not always easy to see or understand. Each person has to determine if and when he or she wants to disclose their autism. If an accommodation is required to do the job, the person is entitled to a reasonable accommodation through the [ADA].”

Paradiz: “Under ADA, of course, the person is not required in any way to disclose their disability during a job interview or any time prior to that. Some people choose to. Some people with autism, especially those [for whom] it might not be obvious right away, many of us fear that kind of disclosure before getting the job for fear of not being hired. … Disclosure is very important and has to be done with a lot of care, and then addressed with a lot of care by the employer when it happens.”

Wells-Herzog: “Sometimes there’s other things going on where we just have to talk about it right out in the open, and the person understands that. The family understands that.”

Paradiz: “For the person on the spectrum, they need to have skills in advocating around their differences and, you know, be able to share with co-workers … almost like an ambassador to the condition, right? Almost, like, assist co-workers in understanding or in an educational way. Like … ‘If you don’t see me at the staff party, it’s because it’s loud and I don’t do well with really unstructured social conversations.’ And usually when people hear that, it helps them understand the differences of autism.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)