Coyote encounters: Do you know what to do?

Workers can take steps to help avoid a conflict

It’s lunchtime, and a landscape worker eating outside drops part of his sandwich on the ground and doesn’t pick it up. Later that day, he sees a coyote lingering in the area. The animal stands there, making the worker uneasy and unsure of what to do.

Coyotes inhabit every state but Hawaii and continue to “colonize” numerous large metropolitan areas thanks to their savvy and an increasing comfort around humans, said Stanley Gehrt, professor of wildlife ecology at Ohio State University and director of the Chicago-based Urban Coyote Research Project, which studies and tracks the animals in six northern Illinois counties.

These factors increase the likelihood that workers, especially those whose jobs are outdoors, may encounter a coyote.

‘No evidence that they’re slowing down’

Pinpointing the number of coyotes nationwide is difficult, but a steady volume of sightings suggests “no evidence that they’re slowing down in terms of their population growth,” Gehrt said.

Why? As coyotes move into more metropolitan areas, the leading risks to their existence in natural or rural environments – hunting and trapping – disappear. Meanwhile, urban food sources have emerged in the form of rodents, rabbits, squirrels, and even small domesticated dogs and cats.

“Once the coyotes figure out human activity patterns, and especially traffic patterns, then they’re able to exploit the urban environment really, really well,” Gehrt said. “And then once they get established, they have higher survival rates, they have a higher reproductive rate because of that food. Then it doesn’t take long for you to have a pretty robust coyote population.”

In general, coyotes “are more afraid of us than we are of them,” said Lynsey White, director of humane wildlife conflict resolution at the Humane Society of the United States in Washington. “So, what a coyote should do if they see you is to run away from you.”

However, what about a coyote that loses the instinct to avoid humans?

Aware of awareness

Although most coyotes in urban areas have adapted to be more active at night, people don’t often realize they’re close to coyotes during daylight hours because the animals keep themselves well-hidden, Gehrt said. Since the program began in 2000, the researchers have documented coyotes in various discreet locations – under a bench in a shopping mall parking lot, for instance.

Using golf course greenskeepers and other outdoor maintenance workers situated near green spaces as an example, Gehrt noted that daytime encounters between humans and coyotes – whether seen or unseen – don’t have to be recipes for conflict.

“They’re not ignoring people at all – they’re aware,” Gehrt said. “But they know that unless some people show some indication that they know that they’re there, they won’t get up and run.”

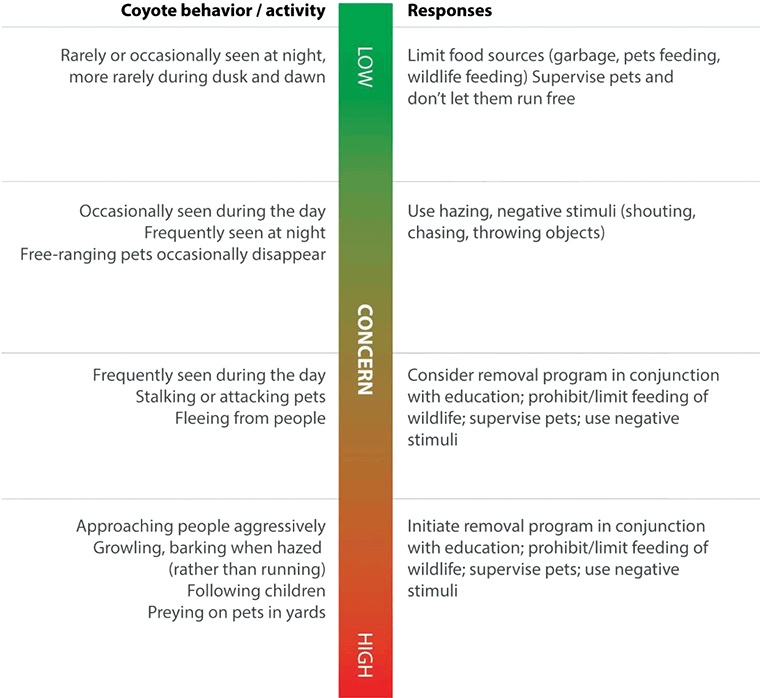

So where does that leave a worker who sees a coyote? The recommended behavior depends on the perceived level of threat.

“The most important thing is that coyotes need to have a fear of people – that’s the only way for them to be able to live with us without conflict,” Gehrt said. “And that seems paradoxical, but that’s the way it works. And it’s important that people don’t do things to let the coyote feel more comfortable being close to them.”

Guidelines to help keep coyotes from getting comfortable around people include:

Don’t feed coyotes. Gehrt recalled a case in which workers eating lunch saw coyotes and intentionally left food for them. Even though some people enjoy seeing animals up close, this is a no-no.

“What happens is when they start feeding them, then that animal becomes more habituated, and it’s not just habituated to those particular workers, but also to other people, as well,” Gehrt said. “And that’s when you start getting complaints about them.”

According to Urban Coyote Research Project findings, 30% of the 142 coyote attacks on humans reported in North America from 1960 to 2006 involved intentional or unintentional feeding near the site of the attack before the incident.

Eliminate wildlife food sources around the work area. Avoid the use of large bird feeders and prohibit feeding other wildlife that may be found in an office park, such as ducks and geese. Also, food scraps that humans leave behind may attract squirrels and other prey, which in turn attract coyotes.

Fasten garbage lids securely. Loose garbage may also contain food scraps that lure coyote prey.

In an email to S+H, an OSHA spokesperson wrote that Urban Coyote Research Project guidance can be “useful for workers and the public.” The spokesperson added that OSHA recommendations found in the agency’s Rodents, Snakes and Insects QuickCard can apply to wild or stray animals. The resource advises workers to avoid contact with such animals and to seek medical attention right away if bitten or scratched. (Download the QuickCard.)

‘Go away, coyote!’

Should a worker spot a coyote, experts advise “hazing” it – described by the city and county of Broomfield, CO, as using deterrents to move an animal out of an area or discourage an undesirable behavior or activity.

“That’s actually a normal thing for coyotes to do. They do a lot of just watching,” Gehrt said. “And that’s the opportunity to teach that animal how it should behave. That’s when the person should yell at them. Tell them to go away. And [shout], ‘Go away, coyote!’ and wave their arms. And that animal should run away at that point.

“If it doesn’t, and the person is uneasy about that, then they should go back and call animal control or a similar agency to record the complaint. … But, usually, it never gets to that point.”

The city and county offer the acronym SMART to help recall proper hazing behavior:

| S | top. Don’t run. If you do, the coyote may chase. |

| M | ake yourself look big. Put your hands over your head or pull your shirt or jacket up over your head. Look as big as you can to scare off the coyote. |

| A | nnounce forcefully, “Leave me alone!” Repeat if necessary. This lets the coyote know you’re a threat, and it lets people around you know that you may be in trouble. |

| R | etreat. Back away slowly. But don’t turn your back on the coyote. |

| T | each your friends and neighbors about coyotes, and instruct children to report coyote encounters to adults. |

For coyotes that have lost their fear of people – often as a result of being fed – hazing can reestablish that fear while informing a coyote it doesn’t belong in a certain area. It may take two or three hazing attempts to get a coyote to change its behavior, but the animal eventually should adapt and communicate to its family group to stay away, White said.

“Hazing doesn’t work if you’re inside a vehicle or inside a house because the coyote is not associating that noise with the person,” White said. “They’re associating it with a vehicle, for instance, and coyotes are very used to vehicles. So honking a horn, for example, that’s not going to be effective.

“A coyote needs to see you and know that the noise or the action is directed toward him from a person, and that way he will associate that to the fear of people.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)