Building better data

Advancing external cause-of-injury coding – e-codes – could make workers safer through more accurate off-the-job safety programs

By Kyle W. Morrison, associate editor- The use of e-codes could lead to better-focused injury prevention programs.

- A growing number of safety and health professionals are pushing to improve data collection throughout the country.

- Several hurdles to the recording of e-code data exist, including cost and time.

- Only 27 states mandate e-code collection.

When your employees are injured on the job, you know where, how and why the injury occurred. In response, you can initiate training or set up new safety guidelines to avoid similar incidents in the future.

But what about when your employees go home? Despite your best efforts at keeping your employees safe on the job, the ratio of them being injured off the job is nearly 3-to-1, according to the National Safety Council. Unlike a worksite incident, you may have no idea of the circumstances surrounding an off-the-job injury.

“When it comes to trying to put a finger on where our employees are getting injured, we know what there is to know about workplace injuries,” said Steve Young, national safety director for Yoh, a Philadelphia-based contract consulting and outsourcing company. “What we don’t know is why people aren’t coming back Monday morning for injuries they suffered at home.”

So how do you set up an injury prevention program when you don’t even know what kind of situations you’re trying to prevent?

The answer is that you can find out, and if some safety advocates are successful in spreading the use of a certain type of data collection, employers may have all the information about off-the-job injuries they will need to ensure the most targeted prevention programs.

Follow the data

“You really have to have a firm grip of what’s going on if you’re going to put in place a policy or program that’ll hit the mark,” said Mel Kohn, acting director of public health in Oregon. Kohn is one of several individuals pushing for the improvement of external cause-of-injury coding, commonly referred to as e-codes.

E-coding is an international system used for classifying injury incidents. The code distinguishes between whether or not an injury was caused by an assault, was unintentional or was self-inflicted. The coding also shows how the injury occurred (e.g., from a fall down stairs or motor vehicle collision). The data is anonymous, but can offer certain characteristics, such as the age and gender of the injured person, and in what region the injury occurred.

“From an injury prevention point of view, I don’t care how many fractures we have compared to how many fractures from falls,” Kohn said. With e-code data, a safety professional is able to identify those specific cases and learn the circumstances of the injury.

Having such knowledge allows a safety professional to develop appropriate injury prevention programs. For example, if the data shows a number of individuals suffer falls from ladders while decorating for the holiday season, a company can put together a campaign on ladder and holiday safety in November.

The data itself comes from hospitals. About 50 million people are treated in hospitals for injuries every year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Doctors treating patients write down information about the injury on medical charts. That information is later translated into e-codes, generally by a trained coding specialist. The more detailed the information in the medical chart, the more detailed the code can be.

“Detailed documentation on injury circumstances in the medical chart is critical to obtaining more specificity in e-coded data,” said Lee Annest, director of the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control’s Office of Statistics and Programming at CDC.

Coding problems

Those specific e-codes can give a safety professional a very good idea as to under what circumstances his or her employees are getting injured.

“The problem is that not all the states do it,” Young said. “Not everybody does it consistently. There isn’t any real mandate.”

According to a CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published last year, 27 states and the District of Columbia mandate the collection of e-codes. An additional 14 states routinely collect e-codes, but have no mandate to do so. Four have a hospital discharge data system, but do not routinely collect e-code data. The remaining five have no statewide hospital discharge data system.

Of states that have a mandate, the quality – including completeness, specificity and accuracy – of e-code data varies, and there is no single standard for quality assurance programs, according to Annest.

Accuracy and specificity is an issue; one of the coding options can be “unspecified.” In that case, the coder may not have known what the code should be for a certain location, or the clinician may not have written in the medical record where the fall occurred.

“The curse of all safety professionals is ‘unspecified,’” said Tess Benham, program manager at the National Safety Council, who is involved in e-code improvement efforts.

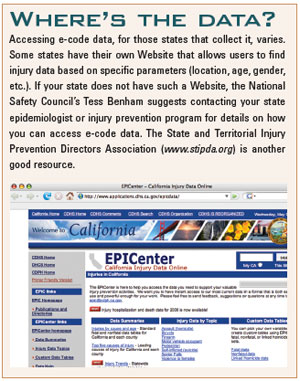

Even the availability of the data varies from state to state. Some states, such as California, have a Website where one can go and find the data for all types of injuries and situations. Other states may not have the data so readily available to the public or presented in a clear manner.

Annest said it is important for data to be easily available and for communities to know how to use it to design injury prevention programs. “There needs to be a central location, a repository where someone can go and get the information,” he said.

The formation of such a repository leads to another problem associated with e-codes – cost. Training for coders and hospital staff or implementing a quality assurance program may be only cents per code, Young said, but that adds up. He suggested that the cost associated with coding be recouped through marketing the data.

Whatever the cost may eventually be to the states, medical professionals and employers, Kohn said it is minor compared to what will be saved in the long run with better data and improved injury prevention programs. “I think the analysis is that the increased cost is very, very small, particularly when you compare it to the benefit to society as a whole,” he said.

More critical than cost, though, is time. Accurate data for e-coding relies on the time a doctor takes to write down the information surrounding the injury – time the doctor may not have. “Every second you take filling out paperwork is going to be time not spent caring for a patient,” Young said.

From a health care provider point of view, they may question why they should be bothered to collect the data if there is no mandate or if the collection is not tied to reimbursement. “That’s a big hurdle – to convince people that the data is worth collecting and it could be useful to them,” Annest said, pointing out that e-code data could be useful to the medical care industry as an indicator to the quality of care given.

Improvement

“Now is the right time for making the case for injury codes,” Benham said, noting the recent push for electronic recordkeeping. Depending on how the programming is set up, it could facilitate the collection of better data. For instance, Kohn said, while a doctor is filling out an electronic medical record, the computer program could force him or her to input necessary information for the e-code.

Regardless of what eventually happens with electronic recordkeeping, Kohn hopes the designers would at least include space in those systems for the recording of e-codes. “I think as the systems are being designed, the architecture needs to be built in a way that at the least won’t inhibit e-code recording, and at the best make it very easy for hospitals and clinicians to collect that data,” he said.

Other ideas for improving the collection of data are coming. Last summer, several federal agencies that use e-codes came together to collaborate on improving the collection of the data. Another meeting was held this past February in which CDC met with several other groups consisting of industry representatives and nonprofits – including the National Safety Council. The groups discussed actions to put in place that might further the effort.

“I think we’re making progress,” Annest said. From the meeting, the groups established action plans in four different areas:

- Improving communication and collaboration among stakeholders on e-code data needs in the health care setting, at work and at home

- Demonstrating a business case on why high-quality e-code data is needed

- Improving the collection of quality e-code data from hospitals

- Improving and marketing the usefulness of high-quality e-codes for design, development and implementation of injury prevention programs

Strategies of how to accomplish these plans are expected to be published in the fall, Annest said. Additionally, Annest is co-chair of the CDC Workgroup for Improvement of External Cause-of-Injury Coding, which wrote last year’s MMWR paper discussing the value of high-quality e-code data and providing strategies for improving e-coding.

One of the recommendations in the report was for CDC to examine how mandating e-code collection could improve data completeness and specificity. States that have mandates have, on average, a higher level of completeness to the data, according to Annest. However, Colorado has no mandate but has a 98.8 percent completeness record, according to the report. The Colorado Health and Hospital Association, which manages the state’s hospital discharge data system, worked with trade organizations and hospital chief executive officers to show how they could benefit from data collection.

Further improvement can come from expanding the information that can be taken into account for coding. Current guidelines stress that the information that specialists use should come primarily from the doctors’ notes. Annest would like to see those guidelines changed to allow specialists to use all of the information in the medical report, including that from a nurse or emergency medical technician. The more information the specialist can use for coding, the more accurate the information becomes for formulating future injury prevention programs.

Other little things can be done, Annest said, including spreading the word about e-code data through Web-based fact pages, brochures or a Wikipedia entry.

In the near future, Benham hopes safety professionals and communities are able to access accurate e-code data to create prevention programs. Without such data, any prevention program could be off-center, she warned. Benham gave the example of suicides: Data on deaths shows men older than 65 are the most successful at suicide, but e-code data indicates the most attempts at suicide are by young women ages 18-24.

By knowing what group you want to focus on and using e-code data to learn how that group is being injured, you can put together a targeted prevention program.

“Ultimately, we’ll be saving lives because we’re able to provide correct intervention programs,” Benham said.

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)