Job Outlook 2013

Safety professionals report job stability, but some say their titles fail to reflect their responsibilities

In the environmental, health and safety profession, the same title can have a very different meaning from organization to organization. A safety coordinator may run the entire safety program. A safety supervisor may have no direct reports. And some EHS professionals focus on traditional safety areas, while others spend most of their time on the environmental side.

Findings from Safety+Health’s annual Job Outlook survey show that despite wide variation in titles and duties, many safety professionals face similar challenges in 2013 – including being given more duties without a commensurate boost in title or pay, having limited authority to make changes, and being short-staffed.

As a coordinator who works in government said, “I have more responsibilities than my title conveys. Upgrade my position or lighten the load.”

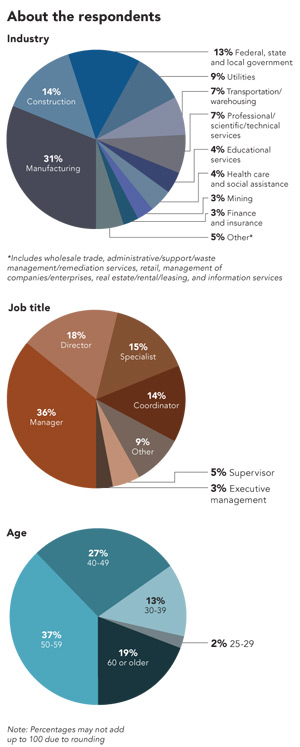

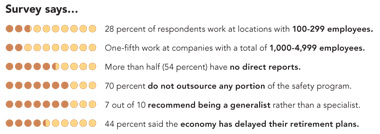

The survey, conducted in February, was sent to 19,417 S+H subscribers – 1,363 of whom responded for a response rate of about 7 percent.

Job security remained high, with 47 percent of respondents rating their job “relatively stable” and 39 percent “very stable.” Almost one-quarter of respondents plan to add staff in the next 12 months. However, most respondents said they have not made staffing changes recently and do not foresee doing so in the next 12 months, which fits with the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ projection of slower-than-average employment growth (9 percent) for safety professionals through 2020.

Sixty-two percent of respondents said titles and responsibilities are inconsistent across the field, and 23 percent said their own title did not accurately reflect their duties.

A respondent in manufacturing explained, “My title is safety leader yet I oversee safety corporatewide (six locations across the USA). With the responsibility for all of it, I should be the corporate safety director.”

Several coordinators felt shortchanged. “I am managing the EHS functions, not coordinating them,” one said.

The issue is not simply one of semantics, but of what leverage and resources safety professionals have to make improvements. “In my current position I do not have the authority, freedom or support to achieve what is needed to accomplish what I feel [is] necessary to have a proper exemplary safety program,” a director in the manufacturing industry said.

The American Society of Safety Engineers in Des Plaines, IL, provides guidance on job roles in its document “The Employer’s Guide to Hiring a Safety Professional.” According to ASSE, one step above entry level is the position of safety practitioner/technician, which requires hands-on EHS experience such as maintaining recordkeeping systems and conducting training and inspections. Next up is the manager/senior technical specialist, whose background should include working with senior management to design safety programs and managing a facility’s safety program. ASSE follows that with director/senior management, a level associated with overseeing safety at multiple facilities and managing subordinates. At the top is the executive vice president, who should have experience running safety corporatewide and interacting with executive management.

During his career at various companies, Steven Ryan has had the same responsibilities under different titles, including safety manager, safety leader and safety specialist. Ryan is now EHS specialist at Pittsfield, MA-based Saudi Basic Industries Corp.’s Innovative Plastics division. He said he prefers his current title of specialist because “manager” implies someone who has direct reports, which he does not.

“That’s more common just in the business place. If you’re a manager, you’re usually managing something and someone,” Ryan said.

Yet results of this year’s survey indicate this is not a uniform practice. Among managers, which made up the largest share of respondents, 41 percent do not have any direct reports. (Overall, 54 percent of respondents have no employees reporting directly to them, and 28 percent have one to five direct reports.)

A manager respondent in the manufacturing industry explained why coordinator or specialist would be a more appropriate title. “My ‘manager’ title implies that I am the head of an entire department. The reality, however, is that I am a one-man department, even though I oversee more than a dozen facilities in several states.” Likewise, one supervisor noted, “My job title is supervisor but I have no one to supervise.”

Some respondents believe their title undervalues their contributions to the organization and could have an impact on their individual careers. For example, a safety administrator said being called an “administrator” carried the connotation of being a “paper pusher.” A specialist said the designation did not qualify him for bonuses and involvement in management decisions.

The latter comment highlights the issue of being in a position to influence the direction of the organization, which safety professionals say is critical.

Mike Clark has been a safety manager at Ames, IA-based AgFeed USA LLC for almost six years. Regardless of title, he said, the highest ranking safety professional must have a “place at the table” with the company or business unit’s leadership team.

Clark said he has found that achievement and skills matter more than titles when looking for a new job. “If you have the experience, the technical knowledge and ability to interact with varying levels within an organization, those are what matters,” he said.

A company title is not the only marker for career growth in safety, according to Kelvin Roth, director of EHS for Hoffman Estates, IL-based AMCOL International Corp., which produces specialty materials. Roth is the immediate past-president of the National Association for Environmental Management, a professional organization in Washington for EHS and sustainability leaders. He defined advancement in terms of increasing responsibilities. In 10 years at AMCOL, he said, his role has grown from plant safety to include lean manufacturing, product stewardship and sustainability.

For safety professionals seeking a promotion or additional resources for the department, Roth advises using the language of senior management. Safety has a set of acronyms and language that safety professionals are comfortable with, he said, “but none of that means anything to senior management. Senior management doesn’t tend to ask you questions in terms of safety. … Your answers and the way you communicate needs to be in terms of business.”

Safety professionals are faced with many different kinds of responsibilities, often without an adequate-sized staff to meet the demands. In the survey, a senior EHS manager said doing a good job with a three-person staff at a company with 5,000 employees was “extremely difficult” and “frustrating.”

Heather Humphries, director of EHS at Lakeville, MN-based Ryt-way Industries LLC, can relate. The company has roughly 800 employees, she said, and while each function typically has four to seven employees, she has only one-and-a-half. The half is an administrative assistant she shares with a plant manager, and she will be losing the assistant because of budget constraints.

Being short-staffed requires organizational skills and prioritizing. “Essentially you have to make the decision: ‘What do I have to do right now that’s going to keep employees most safe?’” Humphries said. That means the vice president may have to wait a few hours for data he requested so she can complete training classes, she added.

Another tip is to recruit other workers to help with safety activities so the safety professional can focus on high-priority issues. Humphries used the example of asking and training supervisory staff and safety committee members to perform incident investigations.

Also, safety needs to be ingrained in the organization, making it everyone’s responsibility. Humphries said many EHS professionals tend to hold on to things they consider part of their job, but progress on safety comes when an organization – not just an EHS manager – owns safety. “The more you can give the ownership to the employees and the rest of the staff, the less the safety professional has on their plate,” she said. “This is crucial when you have limited or no resources.”

Roth agreed. “Even though safety professionals are really good at preaching that safety is everyone’s responsibility, the reality is we too often feel that we need to carry a bigger load, and for programs to truly be successful they have to be integrated into what a company is doing,” he said.

For safety professionals who are a department of one – as Roth was for his first five years at AMCOL – the ability to influence becomes more important. Roth said he concentrated on engaging employees to build a safety culture and, once he did, safety gained a higher profile within the organization, which made adding employees an easy sell.

Two areas safety professionals may be asked to address are sustainability and environmental issues. Both require knowledge of different laws and processes than safety, but embracing another discipline may improve career opportunities.

Roth said being involved with sustainability presents a career advantage because it cuts across the whole organization. “You can’t have one department being sustainable and another department not,” he noted. “It really has to be woven into the fabric of the company, and because of that … it is a good growth path because you’re interacting not only with operations but also marketing, product development, sales, even logistics and supply chains, because all of those play a role in sustainability.”

Michael Miozza, senior EHS manager for Providence, RI-based GTECH Corp., which makes lottery and gaming technology, expanded into the environmental side of the job – but the change was not by choice.

“I can remember saying to my boss, ‘I’m not an environmental person. I don’t have that expertise,’” he said. However, Miozza became an environmental professional through learning on the job. Looking back 20 years later, he is thankful for the experience because it made him more marketable. “Anytime you can take on more responsibility and have more knowledge, I think it makes you more valuable to an organization,” he said.

Miozza expects employers to continue to ask more of safety professionals, so he recommended that his peers accept their broader role and adapt to it.

“At the end of it, just look at the professional growth you’re going to have by going through this process,” he said. “I had a lot of frustration, but then at the end of the day my professional growth was profound.”

Advice for moving up: Safety professionals offer tips

Build your network. Kelvin Roth, director of EHS for Hoffman Estates, IL-based AMCOL International Corp., said networking is vital for safety professionals. He recommended joining safety associations and taking the opportunity to compare against other organizations – otherwise, he asked, how can you know your program is truly world-class? “There are a lot of great professionals and a lot of great programs, and if you’re not benefiting from their mistakes and their successes, then you’re missing opportunities to become more efficient and improve your program,” he said.

Never stop learning. Safety professionals of any experience level can benefit from training to expand their knowledge base. Steven Ryan, EHS specialist at Pittsfield, MA-based Saudi Basic Industries Corp.’s Innovative Plastics division, picked up process safety management skills a few years ago and, when the opportunity arose, he urged his employer to create a position for him based on that expertise. “Basically I identified a need and pushed for it and was able to sell it,” Ryan said.

Think corporatewide. Look for opportunities to help with initiatives that affect the entire organization, not only your department or facility. For example, join a team that is standardizing incident investigations or developing recommendations to improve safety culture. “Maybe it’ll help other opportunities develop if you get on these teams,” Ryan said, “and, if anything, it broadens your experience level, and if you decide to move to another company, experience is key.”

Show off progress made. “I think the important thing if you want to advance isn’t so much titles, it’s results. So you kind of, in some respects, need to blow your own horn and show the progress that has been made in reducing accidents, reducing incidents, reducing costs, those kinds of things,” said Mary Eriksen, human resources and safety manager for Sapp Bros. Inc. in Omaha, NE.

Be a problem solver. Stephen Wilson, corporate director of safety, health and environmental affairs at Irving, TX-based Flowserve Corp., said safety professionals should work hard to anticipate questions and be ready with the right answer. “Be seen as that individual who can solve the hard and intractable problems,” he said. When faced with challenging safety issues, keep things in perspective, Wilson said. “Young people especially can kind of get frustrated and they need to remember that if there were no problems, you wouldn’t be needed,” he noted.

– AJ

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)