COVID-19 and working women

The pandemic is creating some unique challenges

In industries predominantly made up of women, notably health care, as well as those in which women aren’t well represented, including construction and the trades, female workers are facing unique challenges amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The impact of COVID-19 on female workers must be a high priority because women dominate very high-risk jobs such as health care,” said Juliana Ruggieri, training coordinator at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and vice chair of the Women’s Division at the National Safety Council.

Health care

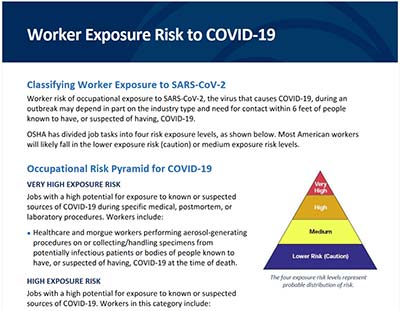

In March, OSHA published a chart to help determine workers’ risk level for exposure. The four-tiered chart is based on a hierarchy of occupational risk, from “very high” to “lower (caution).” Health care workers fall into the “very high” risk group. Among them are nurses, more than 80% of whom are women, according U.S. Census Bureau data.

An effort to research the number of nurses whose deaths are linked to COVID-19 led Deborah Burger and her colleagues to a grim task.

“We started trying to track it by looking at the obituaries,” said Burger, president of National Nurses United and the California Nurses Association. “It’s not tracked anywhere.”

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Protection shows that, as of July 8, 512 health care workers died as a result of COVID-19. However, the agency noted that health care personnel status was available for only 21.4% of the nearly 2.5 million people for whom it had data. Burger and NNU, which represents more than 150,000 registered nurses nationwide, believe strongly that female workers have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19.

Burger, a 45-year nursing veteran, expressed frustration with the federal government regarding personal protective equipment. “From the very outset, the CDC had the highest standard” for the use of a controlled air-purifying respirator or powered air-purifying respirator when caring for patients during procedures generating aerosolized particles, she said. “Almost everything in intensive care is generating aerosolized particles. Then N95s became the floor. ... (Eventually) it was, if you can’t get a CAPR, an N95 or a surgical mask, you can use just a paper mask or a bandana or a scarf.”

Now, months into the pandemic, Burger said nurses are reporting persistent shortages of PPE at their facilities. She said she found her own N95 masks at a California safety gear store, while her husband located some at a feed store.

NSC Women's Initiative

To help people live their fullest lives, from the workplace to anyplace, NSC is working to increase female participation in the safety industry.

The trades

While health care workers deal with reported shortages of PPE, women in trades face a long-standing dilemma.

“Workers come in all shapes and sizes,” said Chris Cain, executive director of CPWR – The Center for Construction Research and Training. “Tradeswomen are typically smaller than the average construction worker, and one long-running concern is poorly fitting PPE. This is even more significant during this pandemic, where properly fitted respirators are needed when workers are in proximity.”

A survey of 445 tradeswomen in the United States and Canada on the impact of COVID-19 conducted in March and April by Chicago Women in Trades – a training and advocacy organization for female workers – found that respondents identified improperly fitting PPE, unsanitary bathrooms and lack of handwashing facilities as three of the most common concerns on jobsites. All three can cause concerns about a lack of protection against COVID-19.

“Building and construction trades workers regularly work on jobsites that are notorious for their lack of cleanliness and unsanitary conditions,” CWIT Director Lauren Sugerman said. “Most sites rely on limited unhygienic toilet facilities that are not cleaned or changed out every day.

Moreover, handwashing stations are not a (common) feature of jobsites. And, even if they were, workers regularly share tools, hold a ladder, climb a scaffold and commonly work with materials many other workers touch.”

Additionally, only 28% of the respondents said they had facemasks and other PPE to use on the job. “This is unsurprising, as jobsite safety and hygiene are not new issues for tradeswomen,” Sugerman said.

People in the trades also tend to work in teams and in confined spaces. On its Women in Construction webpage, OSHA says women should test employer-provided PPE for fit and comfort, and that protective gear worn by women should be based on body measurement data. Proper fit is important to ensure workers are effectively protected from hazards.

“If the provided PPE is uncomfortable, or not suitable for the worker, they should report this condition to their employer for a suitable replacement,” the agency says.

Pregnant workers and parents

Results of a CDC study published in June raise concerns about the effects of COVID-19 on women who are pregnant. Because women experience “immunologic and physiologic changes” during pregnancy, they might be at increased risk of more severe respiratory illnesses, researchers concluded.

Although they don’t have a higher mortality rate, pregnant women also are 1.5 times more likely to be admitted into an intensive care unit and 1.7 times more likely to receive mechanical ventilation, the researchers found.

The researchers, who looked at laboratory-confirmed cases between Jan. 22 and June 7, determined that measures to prevent infection should be emphasized to reduce the occurrence of severe illness among pregnant women. Potential barriers to adhering to these measures also should be addressed.

For parents of young children, COVID-19 has led to a whirlwind of changes, with schools and day care centers closing while some of them work essential jobs. A nationwide survey of 800 parents of children younger than 5 conducted between March 31 and April 4 by the Bipartisan Policy Center and Morning Consult found that 63% of respondents working during the pandemic had difficulty finding child care. Among those working in person, 49% said they needed child care, while 21% were reducing their work hours to care for their kids.

“All parents are finding it especially challenging now balancing work and family demands,” Cain said, “and in a lot of families, women take the lead in parenting.”

The road ahead

After dozens of states experienced rises in COVID-19 cases in June and July, experts say employers should focus on a multipronged effort to keep workers, including women, safe and healthy. Along with taking physical precautions, mental health must be considered. Initiatives such as the National Safety Council-led SAFER: Safe Actions for Employee Returns offer guidance.

“Some of these guides focus on stress management, building resilience and managing workplace fatigue, which can be introduced into an existing or new employee safety program,” Ruggieri said. “As COVID-19 continues to impact female workers significantly, businesses must be flexible and dynamic in their response to worker health and safety.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)