2009 State of Safety

The recession's potential impact on injury rates

By Kyle W. Morrison, associate editor- Historically, injury rates have declined during recession periods, attributed to fewer inexperienced workers and other factors.

- While safety and health departments have, in the past, been the victim of economic slowdowns, some experts do not see that happening this time around.

- The continuing trend of lowering injury and illness incidence rates has been attributed to the emergent safety culture and greater cooperation between businesses and the Department of Labor.

It’s one of the worst economic periods in recent memory. News of the housing market collapse, struggling auto manufacturers and a shrinking job market fill the headlines every week. People are losing their homes and their financial security, but are they losing their literal life and limb, too?

Each year, Safety+Health reviews injury and illness data to examine trends in workplace safety. For this year’s “State of Safety” article, Safety+Health looks into what implications, if any, the recent U.S. financial meltdown may have on safety.

Recessions and receding rates

With the passage of the economic stimulus package and continued collapse of the subprime mortgage market in 2008, there was little doubt as to the financial trouble the United States would face in the coming months. This past November, the National Bureau of Economic Research confirmed what many already believed: The nation was recessing, and had been since December 2007. At press time, only injury data from 2007 was available; the impact of the financial crisis on injuries and illnesses may not be fully understood until later this year, when data from 2008 is published.

However, if history serves as a guide, a downturn in the economy may very well coincide with a statistically significant drop in occupational injury and illness incidence rates for the private industry as a whole. “Things just don’t vary much from one year to the next unless something drastic happens, like an economic downturn,” said Alan Hoskin, who retired in November as statistics department manager for the National Safety Council.

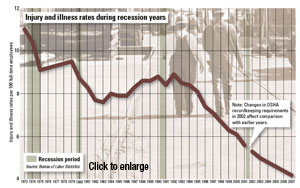

Recessions or economic downturns occur with some regularity. The last recession was from March 2001 to Nov-ember of that year, although that was in the middle of an already established trend of decreasing injury and illness rates. There were 8.9 total recordable cases per 100 workers in 1992, a rate that dropped each year to 5.7 in 2001, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Following the recession, the rate continued downward to 4.2 in 2007. What is interesting is what occurred before the downward trend started in 1992. In 1990, the injury and illness rate was 8.8 per 100 workers, a rate that had been steadily climbing since a record low of 7.6 in 1983. The time period of July 1990 to March 1991 is considered a recession by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, and the injury and illness rate dropped to 8.4 per 100 workers in 1991 before climbing again the next year.

The late 1970s and early 1980s are more examples in which a recession was accompanied by lowering injury and incidence rates. Technically, two recession periods occurred in that era: from January 1979 to July 1979, and from July 1980 to November 1981. During those two periods, the injury and illness rate per 100 workers began at 9.5 in 1979 and fell to 7.7 in just three years.

Hoskin is quick to point out that other causes may factor into these drops. In the 1970s, shortly after the Occupational Safety and Health Act and the formation of OSHA, safety records improved as businesses fell into compliance with the new requirements. Changes to the agency’s enforcement policy also affect rates. For instance, Hoskin said, OSHA began emphasizing its enforcement policy of recordkeeping requirements as part of its inspections in the mid-1980s, leading to companies reporting more incidents. Other policy changes also play a role in decreasing numbers; in 2002, OSHA changed its recordkeeping requirements, making comparisons of recent years to those in years prior difficult.

History repeats?

Despite those caveats, some in the industry see a correlation between recessions and lower injury and illness rates, and predict history will have repeated itself in 2008. “I think there’s definitely a pattern,” said Paul Bartleson, senior director of safety and health at Kraemer Brothers, a Plain, WI-based construction company. He notes various studies that show what occurs during non-recession years, when both money and work projects abound: “There’s a finite number of construction workers in our country. But when demand exceeds supply of labor, the only thing you can shrink, you have to shrink schedules – work done in less time.” The end result of compressing schedules ultimately leads to an increase in incidents.

This is something that has been seen in Las Vegas recently, where several construction deaths occurred during an around-the-clock building boom. However, in a depressed economy, fewer jobs result in production decreases, leading to fewer hours worked and, thus, fewer incidents.

The workers who are more likely to be injured on the job are those who are seasonal or work-for-hire employees who only come on-board for large jobs, noted Carl Griffith, safety and quality director for Trench-It Inc. in Union, IL. “They come with the jobs,” he said of the seasonal staff. “If we don’t get the work, we don’t hire them.”

The workers who are more likely to be injured on the job are those who are seasonal or work-for-hire employees who only come on-board for large jobs, noted Carl Griffith, safety and quality director for Trench-It Inc. in Union, IL. “They come with the jobs,” he said of the seasonal staff. “If we don’t get the work, we don’t hire them.”

Additionally, staff members with more seniority are generally safer, and they are the individuals less likely to be laid off. “There’s definitely evidence that less-experienced workers are injured at a higher rate than more-experienced workers,” Bartleson said.

Another theory as to why rates decrease during a recession is that those who are on the job may be less likely to report an incident, especially a minor one such as a sprain or strain, according to Griffith. This leads to underreporting.

“If you’re one of these people who are part of the core and lucky enough to have your job during hard times, you’re going to think before you report an injury. You may have to take off and be on workers’ compensation,” he said. “All this stuff goes through their minds, and they don’t really report it unless it’s really serious.”

Safety departments safe

The number of workers in the field has already become apparent. BLS announced in December that employment fell 1.9 million since December 2007. More than half of those job losses (1.26 million) occurred in a three-month period (from September to November) and, in November, the unemployment rate was 6.7 percent. Manufacturing and construction were two of the hardest hit industries, losing 626,000 and 568,000 workers since November 2007.

While these figures may be a sign of the continuing economic downturn, some believe they are not a sign of losses in safety departments. Griffith said his safety department five years ago consisted of one person – now 11 are working there. But even in the wake of the latest BLS job report, Griffith, who has been in the safety profession for 40 years, is confident that safety departments throughout the country will remain stable. “It used to be that the first thing chopped out would be the majority of the safety department,” he said. “We are now part of the job.”

Griffith believes companies are likely to spare their safety departments because they have begun to understand the fundamental point of having a safety culture. A better-staffed safety department will be better able to ensure a safer workforce. “If you don’t have a good safety program and have lots of OSHA citations, you’re not going to be able to do business,” he said. “Safety is just good business.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)