Road to rulemaking

The steps OSHA takes to issue a new standard

From proposal to final rule

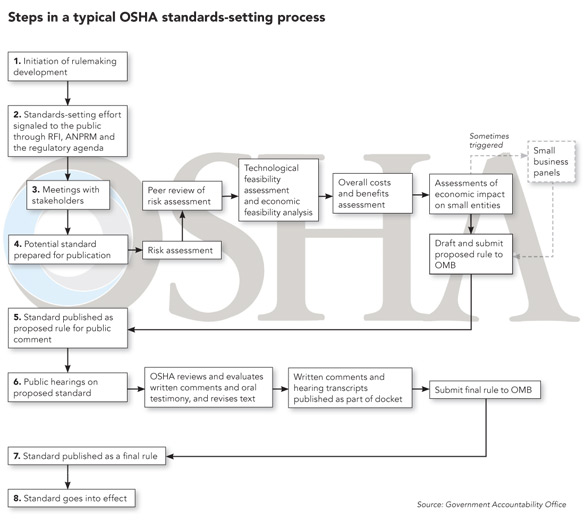

As part of the development of any proposed rulemaking, OSHA must conduct a series of assessments and panels. The OSH Act requires a risk assessment, an economic feasibility analysis and a technological feasibility analysis.

The agency also is required by law to assess a proposed rule’s impact on small businesses and, if necessary, host a panel for small business representatives to provide special input. This is required under the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act for any proposal expected to have a “significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities,” according to OSHA.

However, Rabinowitz said OSHA already is required to look at whether a standard would overwhelmingly impact small businesses, and suggested small businesses should not receive preferential treatment.

“SBREFA might have merits of getting input of small businesses, but they’re free to partake in the rulemaking process,” she said. “I don’t think they should have a preferred say.”

The SBREFA process is not very long – about three months – and can be beneficial, Finkel said. O’Connor agreed, adding that as long as the process does not go on indefinitely, speaking with small businesses can provide value.

Once a proposal is created, a draft is sent to the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, which reviews the rule and recommends changes. OMB and OSHA negotiate on what should stay in the rule or be taken out, or the wording of various sections.

Meetings may take place for stakeholders, OMB and OSHA officials to discuss the rule. In some ways, the OMB review is like another pair of eyes to ensure the rule makes sense and is justified, which is a good idea, Finkel said, despite the potential for the conversations to duplicate other talks. (Read The OMB hurdle for more on OMB’s role in the rulemaking process.)

After OMB approval, a notice of proposed rulemaking can be published in the Federal Register. The public has 60 days to submit comment (this time period can be extended) and participate in public hearings. This stage of the process may cause confusion: The rule published is only a proposal – not the final rule. The agency can and has changed proposed rules after receiving feedback from the public.

“If it’s in the ballpark and someone says the [permissible exposure limit] should be 10 instead of 20, that’s what you learn about the proposal,” Finkel said.

OSHA reviews the comments and, if it determines changes are necessary, revises the text of the rule. The comments and hearing transcripts are published as part of a docket on the proposed rule, which is available for public view. The agency then submits a final draft to OMB for review. After the White House signs off on the rule, it is published in the Federal Register as a final rule and will state when it will go into effect. Any group that believes it is adversely affected by the rule may request a judicial review within 60 days after the final rule was published.

Placing blame

Is the process slowing down to the point it could take the agency decades to put out a final rule? In the 1980s, the agency finalized 24 standards, each taking an average of 70 months from initiation to final rule, according to GAO’s report. The 1990s saw that average time increase to 118 months, but OSHA finalized 23 standards.

In the 2000s, the average time it took OSHA to finalize a rule fell to 91 months, but the output significantly dropped – only 10 standards were finalized in the 2000s.

As the GAO report noted, other government agencies face similar requirements but are able to issue rules at a quicker pace than OSHA.

“It’s clear to anyone who’s watching the situation closely, political interference has been a real obstacle,” O’Connor said. He pointed to the proposed Crystalline Silica Standard – which at press time had been under review by OMB for more than two years – and a Department of Labor regulation regarding child labor safety on family farms that was withdrawn following a fierce backlash to the proposed rule. “It’s not just a matter of following all the legal steps of the process, but there’s clearly been a political message that the administration doesn’t want to be seen as being overly regulatory.”

Finkel suggested that OSHA’s leaders have a “failure of will” to finalize standards in a timely matter, and he is not alone. Rabinowitz said the agency brings a lot of issues onto itself by spending too much time “hand-wringing” over proposals.

“From 500-page regulatory impact analyses to hundreds of pages of Federal Register notices, the fear that someone might question [OSHA] on something leads them to overanalyze a lot of things,” she said.

The agency disagrees with this assertion. The OSHA spokesperson said a “substantial” amount of time is needed to go through all the required risk, economic and technical feasibility assessments within the notice-and-comment framework OSHA must follow.

“The lengthy rulemaking process is something that has transcended recent administrations and is more attributable to increasing evidentiary and procedural requirements, as was noted in the recent GAO report,” the OSHA spokesperson said.

The spokesperson also said it may be difficult for OSHA to speed up the process without a change to the laws, and the agency is attempting to better coordinate within itself and with NIOSH – which was GAO’s sole recommendation for shortening the rulemaking process.

The OMB hurdle

One step in OSHA’s rulemaking process that critics suggest slows things down is the review by the White House’s Office of Management and Budget.

OMB requires OSHA to look at the cost of a rule. Although some stakeholders suggest OSHA’s risk assessment plays a part in slowing down the rulemaking process, Adam Finkel, former director of Health Standards Programs for OSHA, said the real culprit is the economic analysis. Finkel said the analysis is conducted by people inside OSHA, which does not have enough resources or staff to complete the labor-intensive work in a timely manner.

This economic analysis is problematic for another reason, according to Randy Rabinowitz, director of regulatory policy for the Washington-based Center for Effective Government. The analysis is conducted only for the OMB review, Rabinowitz said, and the Supreme Court has ruled the agency cannot use it when creating a rule.

Another aspect about the OMB process that angers some stakeholders is the office’s repeated failure to meet deadlines. Technically, the review process is meant to last 90 days, with a possible 30-day extension. But for several recent OSHA proposals, the review process has extended far longer. Most notable is OSHA’s proposed rule to update its Crystalline Silica Standard, which at press time had been under review by OMB for more than two years.

“What’s going on with silica is just a travesty,” Rabinowitz said. The result has been OSHA stuck in a sort of regulatory limbo, she said, waiting to find out whether the White House will eventually approve or reject the rule. (For more on silica and OMB, read Silica standoff.)

– KWM

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)