Status of the states

In light of a review, OSHA contemplates changing oversight of its State Plan system

By Kyle W. Morrison, associate editor- Twenty-seven states and territories operate their own safety and health program with oversight from OSHA.

- In light of Nevada’s problems, federal OSHA is launching a review of all the State Plan programs and will likely revamp its oversight.

- Many experts highlight a lack of federal funding for State Plans as a source of potential problems.

There was a problem in Nevada. In 2006, the Las Vegas strip was in the middle of a building boom, with numerous large-scale construction projects cropping up on a 65-acre piece of land. In 18 months between 2006 and 2008, 18 construction workers died on those projects. In another 18-month period (January 2008-June 2009), 25 on-the-job deaths occurred throughout the state.

“In Nevada, we have shared the pain of work-related fatalities all too often,” Don Jayne, administrator of the state’s Department of Business and Industry, testified in October 2009 before the House Education and Labor Committee. “Even one work-related death is too many. Federal OSHA and the State Plans must do more to eliminate fatalities.”

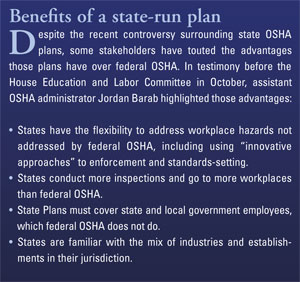

Similar to 26 other states and territories, Nevada is in charge of running its own occupational safety and health program, with oversight from federal OSHA. The number of deaths in the Silver State in such a short period of time and the media attention it brought, coupled with several complaints regarding the Nevada agency’s investigation into a workplace fatality, prompted OSHA to conduct an in-depth review of the state-run plan.

Looking into the problem soon made it apparent to the agency that an even greater problem existed – one concerning federal OSHA and the State Occupational Safety and Health Plan program as a whole.

Changes in oversight

“We were not performing the oversight that we’re required to do,” assistant OSHA administrator Jordan Barab testified during the Oct. 29 hearing on the Nevada OSH plan review.

Barab, who at the time of the hearing was acting OSHA administrator, said the recent review is leading the agency to enhance its own oversight, monitoring and evaluation of state programs.

OSHA will conduct a baseline study on every state that operates its own OSHA plan, according to Barab. Based on the results of those studies – expected to come as early as April – the agency will overhaul its current oversight policies. Additionally, the Department of Labor’s Office of Inspector General recently announced plans to conduct an audit into whether OSHA is fulfilling its role in investigating the complaints of State Plan inadequacies and requiring states to take appropriate corrective action. According to OIG, the audit will be the first federal look at the State Plan program since the Government Accountability Office issued a report in 1994. Referring to the failures in oversight concerning the Nevada program, Barab indicated significant changes were likely to come regarding how OSHA currently oversees State Plan programs. “We’re fairly sure we’re going to need to make some fairly major changes in those current monitoring procedures,” he said.

The oversight method, formerly extensive, has been reduced to a goal-based system in which states are reviewed in a Federal Annual Monitoring Evaluation report in relation to the goals they established. Details on how that oversight may change are sparse, but Barab did note a few ways federal oversight will be enhanced:

- Regional administrators were sent interim guidance on a “wide range” of monitoring tools available, and were encouraged to conduct more extensive investigations.

- Complaints About State Program Administration – filed to federal OSHA regional administrators – will be taken more seriously.

- More special studies will be conducted in response to information collected through routine monitoring, media reports or CASPAs.

Funding problems

A common theme throughout testimony during the House committee hearing, and one many claim is closely linked with a state’s performance, was funding – or, rather, the lack thereof.

“Funding is absolutely the biggest issue,” said Kevin Beauregard, assistant director of the North Carolina Occupational Safety and Health Division. “In order to maintain an effective program and meet the requirements that states are required to meet, it requires funding.”

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Act, states that operate their own plans are required to fund at least 50 percent of the costs for the program, and federal OSHA may not fund more than 50 percent.

Originally, the split was exactly 50-50. Throughout the years, however, states have expanded their OSH programs and federal funding was not able to keep pace. More recently, although federal OSHA’s own budget has grown by 20 percent in the past seven years, the amount of federal money going to State Plan programs has not increased significantly. In fiscal year 2009, federal contributions to State Plans totaled $92.5 million, and states themselves put in about $184.3 million – meaning about two-thirds of State Plan funding comes from the states.

“What happens is many states have put in more state funding to make up for the lack of federal funding,” said Doug Kalinowski, director of both Michigan OSHA and the Occupational Safety and Health State Plan Association. OSHSPA is an organization of officials from the State Plan programs that serves as a link from the states to federal OSHA.

In hard financial times, states can have difficulty putting up more money to maintain the program. In his testimony, Barab noted many state resources committed to OSH programs have been eroded by inflation, and some states have been forced to leave compliance officer positions vacant.

To help, President Barack Obama’s fiscal year 2010 budget request contains a nearly 15 percent boost to State Plan funding. Although this certainly may be welcomed, Kalinowski said some states have difficulty finding funds within their own budgets to match federal funding. This creates a catch-22: States in most desperate need of additional funding cannot receive federal funding because they cannot match it to maintain an even split.

While the idea has been floated of changing the statute to allow federal funding in excess of 50 percent for particular states experiencing financial difficulties, doing so may threaten a State Plan’s autonomy. “Some of the concern is the more money federal OSHA puts in, the more control they’re expecting to exercise,” Kalinowski said. For states that have operated their own safety and health programs since before OSHA came into existence, this could be a point of contention.

Another funding issue that needs to be addressed is the formula to fund State Plan programs. According to Jayne of Nevada (a state that overmatches its federal funding), OSHA needs to implement an “equitable and consistent” formula to fund state OSH programs. “If you want State Plans to succeed, you must address the funding formula,” he said.

An OSHA spokesperson recently told Safety+Health magazine that the current formula has proven unsuccessful in closing the gap in funding levels among various states. To address the issue, OSHSPA formed a task group to propose revisions for the distribution of funds.

A moving target

Although more money or better allocated funding may help improve a state OSH program, how exactly can one tell when it is operating in the same manner as federal OSHA?

“That’s what federal OSHA and State Plans get to all the time: How do you evaluate and make sure you’re doing as an effective job as possible?” Kalinowski said. With numerous parameters to consider, such an evaluation can be complicated, but Kalinowski said it is necessary to identify issues. “If there are problems, let’s find the problems early before they turn into a Nevada-type situation,” he said. The difficulty comes with how that oversight is conducted and what the measurements and benchmarks are. By statute, state OSH programs must be “at least as effective” as federal OSHA in providing safe and healthful employment to workers in the state. When asked during the Education and Labor Committee hearing what benchmarks OSHA uses to quantify “at least as effective,” Barab seemed to acknowledge the phrase’s vagueness.

“Well, that’s the essence of the issue here,” he said. “There are a number of benchmarks we could be using,” including injury, illness and fatality rates in the state; how many inspections are performed; and the seriousness of citations issued. Barab said OSHA would be looking at those measures and would decide which ones are best able to evaluate the states. However, state OSH programs attempting to achieve an “at least as effective” status by hitting some of those benchmarks could find a “constantly moving target,” according to a statement from OSHSPA.

If one of the measures is comparing the state’s percentage of serious citations issued, federal OSHA’s policy decisions have an effect on the outcome, according to the statement given to the committee. For example, OSHSPA said OSHA’s construction policy to exclude issuing nonserious violations when they are abated during the inspection could lead to 100 percent of citations being serious. States that do not follow that policy – and therefore issue citations for other-than-serious violations – would have a lower percentage of serious citations and on paper may look to be doing a less effective job than OSHA when that may not be the case. “I’m not saying those aren’t important issues to look at,” Beauregard said of examining the percentage of serious citations. “What I’m saying is that if you deviate from the national average, it may not have any effect on the effectiveness of your program.”

But federal OSHA is a moving target, and necessarily so, according to the agency spokesperson. When new hazards are identified, OSHA has to respond with standards, emphasis programs or outreach. Because state programs are required to be at least as effective as federal OSHA, they are expected to respond to the changes seen in the federal program. “OSHA attempts to give states ample notice of upcoming changes,” the spokesperson said.

A 50/50 partnership

What concerns some in State Plan programs may not be the amount of time after the changes, but the process leading up to the changes themselves. OSHSPA advocates for a partnership between the state OSH programs and federal OSHA, wherein states are much more involved in the process surrounding policy decisions.

After all, states operating their own plan are able to run the program their way. It is not unheard of for some states to issue standards or programs that do not exist in federal OSHA. “OSHA recognizes that the states have expertise in many areas and attempts to involve states in the process,” the agency spokesperson said.

Representatives from agency directorates meet with OSHSPA three times a year to discuss upcoming regulatory initiatives, state representatives serve on OSHA advisory committees, and some policy directives under development are sent to state offices for review. Additionally, according to the spokesperson, states are encouraged to participate in the rulemaking process and submit comments for the record, and they receive advance notice of proposed and final rules before publication in the Federal Register.

But that may not be enough, according to Beauregard. “The fact of the matter is that when national policies are being developed, or national special emphasis policies are being developed, OSHA does not include, in the majority of the times, OSHSPA member states in the development of those until the very end, when a policy has been drafted and developed,” he said. “A true partnership should include the actual participation process.”

Beauregard pointed out that getting states involved in developing National Emphasis Programs could lead to programs that impact every state. For instance, a recent NEP on refineries would have very little impact on states with no refineries, yet still is considered a national program. While not currently mandatory, OSHA is considering making an NEP a requirement. If that happens without front-end involvement from the states, states would then be asked to disregard their priorities, according to Beauregard.

Neither state programs nor OSHA have all the resources they need, Beauregard said, making it necessary for both to work together to ensure the available resources are used in the best possible way. OSHA should hold itself up to the same standard it asks of the states, he said.

OSHA conducts internal audits of its regions and areas. But these audits on regional and area offices are internal self-evaluations, according to the OSHA spokesperson, and are not routinely made available to the public. “I don’t think any state’s perfect or any federal region’s perfect,” Kalinowski said. “But we can always improve.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)