2016 State of Safety: Changing demographics

A greater number of older workers are staying on the job. How is workplace safety affected?

Key points

- Older workers experience fewer nonfatal injuries than other workers, but take a longer time to recover from their injuries.

- The number of deaths among workers older than 64 has been increasing for several years, and the fatality rate has recently spiked.

- Employers should take steps now to make the workplace safer for older employees, and instill positive safety behaviors in younger workers, experts say.

For years, the number of older workers on the job has been increasing, and that number is expected to continue to rise in the near future.

Older workers bring with them a wealth of knowledge from their years of experience. But they also bring increased risk of on-the-job fatalities and severe injuries. If employers want to stem the potential tide of life-threatening and costly incidents among aging workers, the time to act is now.

“The demographics are changing,” said Ken Kolosh, manager of statistics for the National Safety Council. “With increased prevalence of older workers, most employers do realize this reality is not going away.”

The rise

By 2022, about one-quarter of all workers are expected to be 55 or older, according to Mitra Toossi, an economist with the Bureau of Labor Statistics Office of Occupational Statistics and Employment Projections. Toossi has written several papers on older workforce projections. These projections are based on two data sets: BLS population projections and BLS workforce participation rates.

The increased proportion of older workers is due in large part to the baby-boom generation: adults born between 1946 and 1964 – the period after World War II that saw increased birth rates in the United States.

Unlike the generations before them, baby boomers are staying in their jobs longer. Historically, according to Toossi, fewer individuals continue to work after they turn 55. The rate of baby boomers follows this trend, but to a lesser degree. For example, in 1994, 30.1 percent of workers were 55 and older; 20 years later, that rate was 40 percent.

“Every year since the 1990s, [baby boomers] have been increasing their participation rate,” Toossi said. “This is in contrast to all the other age groups where participation rates are declining.”

This older population keeps working for a number of reasons, according to Toossi. For one, the nature of employee benefits has changed. In the past, employees who retired after 30 years would receive a defined retirement sum. Today, most workers have 401(k) plans, which are susceptible to market fluctuations.

The recent economic downturn likely played a role in some older workers’ decision to stay in their jobs longer as well, Toossi said. Others may continue to work for reasons related to health insurance or because the Social Security retirement age has increased to 67 from 65. And some simply may enjoy working.

“People live longer lives. They live healthier lives, so those who have jobs just cling onto the jobs and they don’t want to give it up,” Toossi said.

The fall

So what effect do aging workers have on workplace safety?

In most cases, older workers are less likely to be injured on the job. BLS data shows that in 2014, workers 65 and older experienced 94.2 injuries or illnesses per 10,000 full-time workers – the lowest out of all age groups, and lower than the rate of 107.1 for all worker populations.

Research has indicated that, beginning at middle age, adults start to accumulate more emotional stability and emotional intelligence, according to Juliann Scholl, a NIOSH health communication fellow. This suggests that older workers not only know how to avoid certain risks, but also are more willing to speak up or point out patterns that could lead to injuries, Scholl said.

However, this doesn’t hold true for all injuries. The incidence rate of slips, trips and falls for workers 65 and older – 49.5 per 10,000 workers – is about double the rate of workers younger than 45. Additionally, older workers take longer than their younger counterparts to recover from injuries and return to the job. The median days away from work in 2014 steadily increased with each age group, beginning with four days for 16- to 19-year-old workers and rising to 17 days for workers 65 and older.

“As people get older, their injuries are more likely to be severe,” said James Grosch, senior research psychologist with NIOSH.

As people age, Grosch said, hearing, vision, balance and respiration tend to decline. It’s gradual, and varies from individual to individual, but it happens to all of us. What might cause only a sprain in a 25-year-old may cause a break in a 65-year-old.

This translates into higher workers’ compensation costs. Bill Spiers, a risk control services manager with consulting firm Lockton, authored a paper in 2013 warning of a “tsunami” that will occur when a greater number of older workers stay on the job.

“The wave is coming,” Spiers said. “As those people stay, it’s my opinion that the cost of those injuries is going to be higher.”

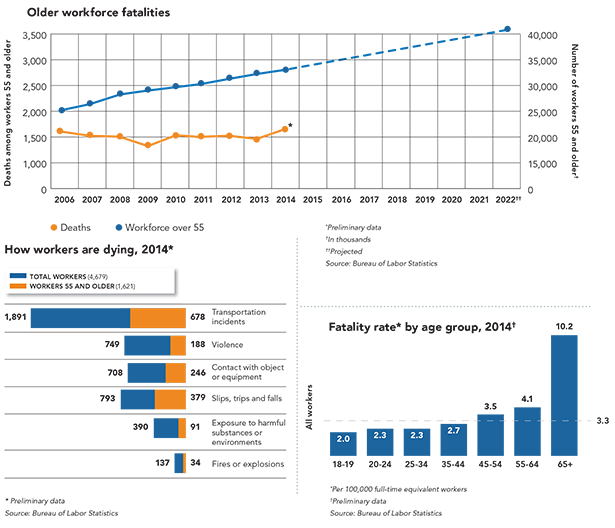

Older workers also are more at risk of work-related death. For several years, the on-the-job fatality rate among older workers has been significantly higher. Preliminary BLS data for 2014 shows that 10.2 workers older than 64 died on the job for every 100,000 workers. In contrast, the overall workforce fatality rate was 3.3.

The number of workers 65 and older who died on the job in the past several years also has risen – to 656 in 2014 from 580 in 2008. With the exception of workers 55 to 64, whose workplace fatalities increased by less than 5 percent, all other age groups saw their total fatality numbers drop during that seven-year period. And between 2013 and 2014, the 65-and-older age group saw the number of worker fatalities rise 17 percent and the fatality rate increase about 8 percent.

“They’re the only age group that had a substantial increase,” Kolosh said. The increase in the number of fatalities is a very large one-year jump, he said, but cautioned that “one year doesn’t make a trend.”

It’s also worth keeping in mind that the BLS figures for 2014 are preliminary. Generally, the overall fatality figure increases when the final data is released, but some preliminary subcategory estimates can decrease, Kolosh said. Statisticians will need to investigate the older worker fatality increase to determine whether a problem exists with the data or if the data is indeed genuine. If it is the latter, more work will be necessary to examine what is driving that increase, as it is outside trends that have been observed.

The future

Although BLS doesn’t project injury and illness figures, Toossi said potential future fatal and nonfatal injury data can be inferred based on current trends and workforce projections.

“What can be correct in the past can show you – not 100 percent – what’s going to happen in the future,” Toossi said.

If the projections are correct, more older workers will be injured and killed on the job, as they continue to increase their presence in the workplace. This potential trend is one several experts are working to prevent.

Both Grosch and Scholl are co-directors of NIOSH’s newly established National Center for Productive Aging and Work. The center will conduct research on best practices for “aging-friendly” workplaces and look at age groups as a whole, not separately, Scholl said.

However, she recommends that employers impart best safety practices among young workers. “The sooner you can instill these habits and practices, the longer it stays with them as they move into an older age,” Scholl said.

Noting that “one size doesn’t fit all,” she added that employers should use multiple approaches to reach a broad range of learning styles. Spiers suggested that employers find the older workers in their facilities, evaluate their ability to do their jobs, and determine whether appropriate precautions are being taken to keep them safe.

Don’t automatically shift older workers away from high-hazard jobs, Spiers said. Instead, consider what accommodations can be made to ensure the workers’ safety. Employers should keep in mind that safety improvements made to protect older workers typically benefit workers of all ages, Kolosh said.

Spiers stressed the need for safety professionals to get ahead of the curve on older workers and start taking action now to ensure a safe workplace. The issue, he said, is not going away.

“Time marches on,” Spiers said. “As a safety professional, it’s my job to look on the horizon to see what’s coming down. This is the next frontier.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)