Golden standard

The successes and shortcomings of Cal/OSHA’s heat illness prevention standard

By Ashley Johnson, associate editor

In August 2006, after several heat-related worker deaths occurred, the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health adopted an emergency heat illness prevention standard. Since making the standard permanent in June 2006, Cal/OSHA has seen a marked decrease in fatalities, although some safety advocates argue the regulation needs additional measures to protect workers.

Exposure to extreme temperatures can cause heat stress, heat stroke, heat exhaustion, heat cramps and heat rashes, according to NIOSH.

In April 2011, OSHA launched a national campaign to educate employers and workers, including those in agriculture, landscaping, construction and road repair, about the hazards of working outdoors in hot weather. The initiative emphasizes providing workers with water, rest and shade, which are core components of the Cal/OSHA standard.

California was the first state to develop a heat illness prevention standard. The Golden State also recently was home to the nation’s first case of an agriculture employer being criminally charged for violating heat regulations. In March, two farm supervisors were sentenced to community service and probation after the 2008 death of a 17-year-old pregnant farm worker who reportedly collapsed in a grape vineyard after being denied water and shade in 90-plus degree weather. The supervisors initially were charged with involuntary manslaughter, but agreed to a plea deal.

Enforcement and compliance

Cal/OSHA’s standard requires employers to provide access to potable drinking water and shade, and to train workers on emergency procedures and recognizing and avoiding heat illness. In 2010, the state’s Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board approved modifications that clarified the shade requirement and mandated precautions for employers in certain industries when temperatures reach 95° F.

For Anne Katten, staff scientist with the Sacramento-based California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation, the rule does not go far enough.

“The revisions helped a little,” she said, “but no, we don’t think the current regulation is adequate for preventing heat illness.”

For example, employers must provide enough shade to accommodate 25 percent of the workforce per shift when the temperature exceeds 85° F (shade also must be available upon request in cooler weather). Katten said enough shade should be provided to cover all employees at the same time. She also would like a requirement that employers have someone on-site trained to provide first aid for heat illness.

Her major concern is with the voluntary recovery period model. The standard allows employees to take a cooldown rest period in the shade for at least five minutes, but Katten argued that many agriculture workers are reluctant to take a break because they are paid per unit or have to meet a production quota. Her solution is for the standard to specify that piece-rate employees be paid for their recovery period at an average piece-rate wage.

Bill Krycia, Cal/OSHA regional manager, said inspectors should check for access to shade during enforcement activities. He said employers have taken novel approaches to providing shade, such as a portable structure called a “butterfly” shade device that is attached to a trailer and can withstand high winds. Some employers also whistle or sound a horn to tell their crew to stop and come in for water.

“The more interaction you get from an employer or supervisor with the employees to make sure they avail themselves of water, shade and rest, the more effective the programs are overall,” Krycia said.

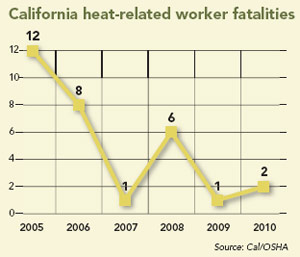

According to Cal/OSHA, employer compliance reached 76 percent in 2010, compared with 35 percent in 2006. Last year, the agency recorded only two heat-related fatalities, in contrast to 12 in 2005.

In addition to training about 1,600 agriculture employers, Krycia said Cal/OSHA reached out to workers through billboards and radio spots; however, language differences continue to present a barrier – workers speak Hmong, Punjabi and different dialects of Spanish, among others.

As for enforcement, Krycia cited a recent sweep during which inspectors shut down a tomato farmer in northern California after finding approximately seven women in the field with no water, shade, communication or training on what to do in the event of an emergency.

Bryan Little, chief operating officer of the Farm Employers Labor Service in Sacramento, helps educate agriculture employers on the regulation. He said most growers understand the requirements and, on hot days, some adjust the workday to begin and end earlier to avoid the afternoon sun.

Little advises putting up shade even if the weather prediction falls just below 85 degrees. Otherwise, employers are “going to wind up getting caught on a day when you should have had shade and didn’t,” Little said.

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)