Harmful exposure?

What is the safety professional’s role in protecting workers’ reproductive health?

- OSHA currently does not have a specific standard for governing reproductive hazards.

- Although a lack of research exists to show direct reproductive effects from hazardous agents, employers and employees can do their part to guard against adverse outcomes.

- The safety professional plays an important role in training workers about reproductive hazards.

By Deidre Bello, associate editor

Reports from the Centers for disease control and prevention showing an increase in infertility among U.S. couples, together with reports of workplace hazards affecting reproduction, have spurred increased concern among some researchers regarding the effect chemical exposures have on reproductive efforts.

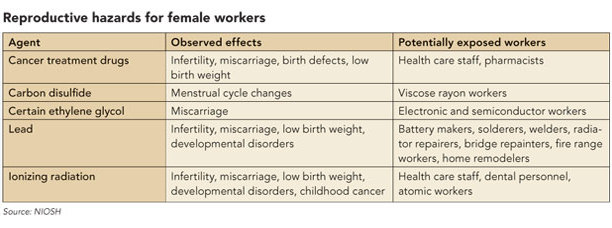

Exposure to chemicals in the workplace can lead to reduced sperm count, affect egg quality, and increase the risks of birth defects and miscarriage, according to CDC. Researchers from CDC and other experts recently called for improved testing, regulation and identification of hazardous chemicals.

Under OSHA’s hazard communication standard (1910.1200), employers have a responsibility to evaluate hazards in the workplace related to reproductive and developmental hazards, and to protect workers – both male and female – from these hazards. What role do safety professionals play in this endeavor and what challenges do they face?

A ‘potentially serious public health problem’

NIOSH has identified more than 1,000 workplace chemicals that cause reproductive effects in animals. (Medical ethics do not allow researchers to test chemicals on humans to study reproductive effects.) Meanwhile, most of the 4 million other chemical mixtures in commercial use remain untested.

In 1999, researchers from the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries recognized the lack of research in its guidance on protecting workers from reproductive hazards. The researchers cited NIOSH’s National Occupational Research Agenda statement on reproductive hazards: “Physical and biological agents in the workplace that may affect fertility and pregnancy outcomes are practically unstudied. The inadequacy of current knowledge, coupled with the ever-growing variety of workplace exposures, pose a potentially serious public health problem.”

Still, according to a report reviewed at the International Labour Organization’s International Labour Conference in 2009, reproductive protection for women in the past half-century has made progress through changes in workplace practice and improved social expectations for women’s rights during childbearing years.

Progress also has been made in safeguarding men’s reproductive health. A NIOSH study of Massachusetts employers during the 1980s showed most companies ignored reproductive workplace hazards for men. Since then, more reproductive epidemiological research on male workers has been documented to examine physical, chemical and physiological exposures, as well as exposure to metals and welding. However, a study published in 2006 in the Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology said workers in other countries still are exposed to high concentrations of substances that cause male infertility.

Marcella Remer Thompson, an environmental health state agency liaison for the Brown University Superfund Research Program in Providence, RI, said although more research is needed on the topic, a proactive approach needs to take place now to address reproductive hazards for both men and women in the workplace. Thompson quoted a common saying among environmental health researchers: “The absence of evidence does not equate the evidence of absence.”

“Just because there is not a lot of research doesn’t mean we should be waiting for these studies to be published to do something about lowering [everyone’s] exposures,” she said.

Research conducted by Thompson has shown widespread prevalence of lead, methylmercury and polychlorinated biphenyls among women of childbearing age in the United States.

“For example, lead, methylmercury and PCBs are neurotoxicants. Since these neurotoxicants bio-accumulate, the body burden from past exposures, as well as those maternal exposures that occur during gestation, transfer to the fetus via the placenta and to infant and child during lactation,” Thompson said.

Her cross-sectional study involved the analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, a national probability sample of childbearing-age females living in the United States from 1999 to 2004. Her study estimated 20 percent of these women had all three of these chemicals at or above the geometric mean in their blood, and an additional 38 percent had two of these chemicals.

“We have to understand the widespread exposure to environmental chemicals both inside and outside of work,” Thompson said. “Each one of these chemicals, these women bring a history with them and it shows that over time, these chemicals bio-accumulate, which means in regards to those women who are pregnant, it opens up this caveat of where and at what point do you address the reproductive hazards. You don’t wait until they’re pregnant. You have to look at, overall, where the workplace is safe.”

OSHA’s role

OSHA currently does not have a standard governing workplace reproductive hazards, but notes adverse reproductive effects in standards for lead (1910.1025), ethylene oxide (1910.1047) and 1,2-dibromo-3-chloropropane (1910.1044). Studies have shown that male workers exposed to DBCP – a pesticide used by exterminators – had a high incidence of infertility associated with reduced sperm count.

Lead exposure, which is common in the construction industry, can be absorbed into the body through inhalation or ingestion, and can lead to stillbirths and miscarriages, while exposure to lower concentrations of lead may result in shortened gestation time and decreased fetal mental development and growth. OSHA mandates monitoring for levels of lead exposure.

Ethylene oxide is a common ingredient in disinfectants and epoxy resins, and studies show it is associated with perinatal morbidity and mortality or miscarriage.

How to protect workers

John Furman, technical services manager for the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries, said reproductive hazards in and of themselves generally are not targeted during a risk assessment. Inspectors look at a chemical or an agent that carries a variety of hazards, including reproductive hazards, he said.

In a majority of cases he sees, Furman said employers are aware of reproductive risks and follow the state’s occupational safety and health standards to limit exposure. Although it is difficult to identify the agents creating adverse outcomes – compared with the cause of a fall or amputation – reproductive hazards should not be ignored, and employees need to know about the potential risks and be trained to guard against them, he said.

Workers also should discuss the risks with their personal physician, Furman said. However, he noted that if a physician believes job duty modifications are necessary and the employee takes those written recommendations to his or her employer, the employer is not legally obligated to follow the recommendations.

“We don’t know what obstetricians are advising their patients,” Thompson said. “For example, only three states (Washington, Maine and Rhode Island) participating in CDC’s Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System ask pregnant women routinely about whether their health care professionals counsel them about fish consumption, mercury exposure and the potential for adverse fetal outcomes related to such exposures.

“There are a lot of gaps in research and practice. Unfortunately the current body of knowledge leaves most health care professionals with more questions than answers,” Thompson said. “Until six months ago, there were no guidelines for lead exposures among pregnant and lactating women. These guidelines from the National Center for Environmental Health are stricter than current OSHA standards for medical removal protection, but silent on when a pregnant woman could return to work.”

Nick Shamsipour, senior safety consultant for the National Safety Council, offered the following tips for professionals and employers to protect workers and guard against legal liability regarding reproductive hazards:

- Conduct a comprehensive risk assessment of the facility to identify potential hazards, especially for employees exposed to hazardous materials or chemicals.

- Train all employees about the chemical hazards they may be exposed to. This can be accomplished by using Material Safety Data Sheets and labels to explain the potential exposure. Also train employees on using proper personal protective equipment when working near hazardous materials.

- Have employees who attend training sessions sign an attendance sheet. Copies of the signed attendance sheet should be filed with the human resources and safety departments.

- In addition to training, print a one-page safety talk and post copies throughout the facility.

ILO encourages safety professionals to acknowledge that the topic of reproductive risks is a sensitive one for workers to discuss, and to determine appropriate methods of gathering information.

Safety professionals also should work with unions and employers to develop policies that allow pregnant women to transfer for the duration of their pregnancy from work known or suspected to have reproductive health effects, and provide similar protection to male and female workers who are planning to have a child, ILO advises. Shamsipour agreed and pointed to a discrimination lawsuit, Automobile Workers v. Johnson Controls Inc., which went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1991. The lawsuit was filed after the Milwaukee-based battery manufacturer banned all women “capable of bearing children” from jobs that would expose them to lead.

Furman said the best way to approach the topic of reproductive risks when training male workers is to clearly associate potential hazards with the particular chemicals or agents the employees are exposed to. Provide them with training on how to minimize their exposures to reduce the risk of an adverse reproductive outcome, he said.

ILO also advises workers to keep a record of their work conditions, as well as the names of any chemicals, biological or physical agents, and potentially hazardous situations to which they may be exposed. Any irregularities or abnormalities that occur in their sexual functioning, menstrual cycle or their partner’s ability to become pregnant should be noted.

Reproductive health resources

Safety professionals can look to the European Union for resources on guarding against reproductive health risks. Under the category “Reproductive Toxicity” in the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals, substances and mixtures with reproductive or developmental effects are assigned to one of two hazard categories: “known or presumed” and “suspected.” Category 1 has subcategories for reproductive and developmental effects. Materials that cause concern for the health of breastfed children have a separate category, “Effects on or via lactation.” In November 2010, CDC published guidelines for the identification and management of lead exposure in pregnant and lactating women.

OSHA is in the process of drafting a final rule to make its hazard communication standard more in line with GHS’s internationally standardized provisions for the classification of chemicals by health, physical and environmental effects; labels; and Safety Data Sheets or MSDSs. According to the agency’s fall 2010 semiannual regulatory agenda, OSHA expects to publish its final rule this month.

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)