Workers' comp

- Workers' comp provides a cost factor not found in other data sources, which may help convince upper management to invest in safety.

- Workers' comp data could provide additional information on the causes or circumstances of injuries and illnesses.

- Each state runs its own workers' comp system, making it difficult to combine and analyze data across state lines for prevention purposes.

Experts say the data could be used to prevent worker injuries. So why aren’t employers using it?

By Kyle W. Morrison, senior associate editor

Many safety professionals believe a good injury and illness prevention program is a must to ensure a safe workplace. Such a prevention program likely will be based, in part, on the company’s injury and illness logs. But are employers also using their workers’ compensation data for prevention purposes?

If not, some experts suggest those prevention programs may be missing vital injury and illness data, and relying on injury data from only one source – such as OSHA 300 logs or the Bureau of Labor Statistics – may fail to paint a clear picture of safety in the workplace.

“There are people who criticize that data and believe it could be more complete, more whole,” said David Utterback, a senior health scientist for NIOSH based in Cincinnati. “It just became clear that additional attention to [workers’ comp data] could help fill in some of the gaps in injuries and illnesses.”

Recently, some safety practitioners have begun to pay more attention to the idea of incorporating workers’ comp data into injury and illness prevention efforts.

Old data, new idea

Workers’ comp laws have been around for about a century in the United States, and insurance is nearly a universal employer requirement. (Texas is the only state that does not require employers to carry workers’ comp insurance.) Despite this, using workers’ comp data for purposes other than compensating injured workers has not been fully explored until more recently.

“We just realized that, looking at the range of available data sources for conducting safety and health surveillance, this is one data source used occasionally – but it hasn’t been used systematically,” Utterback said.

Using workers’ comp data to prevent workplace injuries and illnesses was the main topic of a September 2009 workshop in Washington, D.C., sponsored by NIOSH, BLS, the National Council on Compensation Insurance, and the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries’ Safety and Health Assessment and Research for Prevention program.

About 80 people from state and federal government agencies, academia and the insurance industry participated in the workshop, which included 30 prepared presentations. A report summarizing the workshop was issued the following July, with a revised document subsequently released in August. The report gives an overview of the presentations, which ranged from testimonials of using workers’ comp data at the state or business level to presentations that highlighted using certain types of workers’ comp data.

“We are pleased to offer these proceedings as a unique resource for assessing current uses of workers’ compensation information for health surveillance, suggesting new uses, and engaging the uncertainties that we face in doing so,” NIOSH Director John Howard said in a statement introducing the report.

More information

Although workers’ comp data primarily is used to pay claims to medical providers and injured workers, broader applications are available as a result of that data being collected.

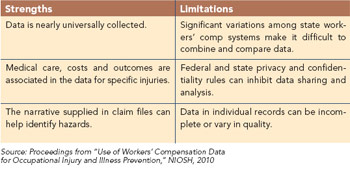

Utterback pointed out that workers’ comp data can be more complete than other data. Many employers are required to keep records of injuries and illnesses, yet OSHA and BLS only collect those records from a fraction of employers. By contrast, the collection of workers’ comp data is greater and may provide a better representation of occupational injuries and illnesses across industries. As such, this supplemental data could lead to better analysis and tracking of injuries and diseases, according to the report.

“These data can supplement the BLS data with richer epidemiological information on the forces causing or associated with injuries and illnesses. They can provide better information about long-run outcomes,” BLS Commissioner Keith Hall stated in the report. “And, these data may identify cases that are not captured by the BLS survey, perhaps because they are outside the survey’s scope.”

The report suggests that use of this larger data pool could lead to more informative analysis of injury and cost trends, and even could help identify emerging health hazards and evaluate the effectiveness of prevention programs.

The cost factor

Among the data collected with workers’ comp that does not typically show up in other data sets is one vital to the bottom line – costs.

Edward Bernacki, one of the NIOSH presenters, is the executive director of health, safety and environment and division director of occupational medicine at Johns Hopkins University and Hospital in Baltimore, which has been using workers’ comp data for injury prevention efforts for nearly two decades.

“You have to control the frequency of injuries, which your OSHA log will give you, but the expense associated with those injuries the OSHA log will not give you. You have to use another metric,” Bernacki told Safety+Health magazine.

That metric can be found in workers’ comp data, he said. In addition to knowing the number of claims, workers’ comp data can be used to learn how much each claim costs for a particular time frame.

Having an idea of what various injuries and illnesses cost both in the short and long term may help show company decision-makers that the interventions are less costly than the various costs of injuries. This may make them willing to invest in preventive measures.

“Upper management doesn’t want people to get injured. But if you can also reduce the cost, that’s big,” Bernacki said.

Consolidation

In many workplaces, workers’ comp or loss control functions may be controlled by separate departments. For employers to get the most out of their workers’ comp data for injury and illness prevention purposes, some experts say safety professionals should have access to it. “[Safety pros] could benefit from having access to workers’ comp data and really understanding what the issues are,” Utterback said.

In 1992, Johns Hopkins created an integrated system in which workers’ comp claims operations became part of the medical treatment and safety program. All elements – from prevention efforts to medical treatment for the injured to claims – talk to and inform one another, Bernacki said.

Johns Hopkins is self-insured and urges workers to use its own doctors (although this is not a requirement). This makes it very easy for someone like Bernacki to access the necessary data to make tweaks and improvements throughout the system. By looking at workers’ comp data, Bernacki found that a lot of employees who were receiving benefits could be working – perhaps not at their former job, but nonetheless doing productive work for either their department or another. In response, Johns Hopkins instituted a transitional program to return injured employees to the workplace as soon as possible.

“It gets them thinking that they’re a worker and not an injured person,” Bernacki said. As a result, the employee is not consuming workers’ comp benefits, which reduces costs – something Johns Hopkins saw in its data after the program began.

Challenges

Despite the potential benefits of using workers’ comp data, challenges remain.

One major problem arises when attempting to use workers’ comp data on a broader scale. Every state has its own rules and regulations concerning workers’ comp insurance, as well as different methods and requirements for collecting the data. As a result, data from across state lines is not always consistent or easily merged, Utterback said.

Another issue is inconsistency in the reports. Depending on the state, the workers’ comp report could be filled in by a doctor or nurse, an employer, or an employee of the insurance company. The data may be incomplete or not properly filled in, leading to gaps, especially if states have different requirements on what information is necessary, Utterback said.

Although these problems are not necessarily an issue within a state, they can hinder prevention efforts on a national scale. This has drawn some attention. Last November, the House Education and the Workforce Committee’s Workforce Protections Subcommittee looked into the issue, and a bill introduced earlier this year aims to create a commission to examine state workers’ comp laws. Such a commission could recommend minimum standards for states to meet. Utterback said this would be helpful.

“Any sort of national standards, be they regulatory or voluntary, would help the data become more consistent across states and ensure certain data elements are collected,” he said.

Utterback doubts a national surveillance of injuries and illnesses using workers’ comp data would ever be created, but said some states could address individual deficiencies to improve the data. In fact, research projects in some states already have begun to use workers’ comp data.

For the employer, access to the data can vary. Employers who are self-insured already have the records on hand, but accounts of access vary for those who use a private insurer, Utterback said. (Some states, including Washington and Ohio, run their own workers’ comp insurance provider.) However, he added, many insurance companies offer services such as site visits to access risk for certain injuries and make recommendations. Some also will aggregate an employer’s workers’ comp data and make it available, Utterback said, but that data might not include indicators of how the employer matches up with others in its industry.

Bernacki stressed that workers’ comp data is not “excess data” – it plays an important role in injury prevention – and he recommended every employer access its data to learn from it. “You have to collect it anyway,” he said. “You might as well use it.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)