Virtual reality and safety training

The benefits – and potential concerns

You don a virtual reality headset. Then, the floor begins to shake and the sound of an “industrial whine” is heard as you shoot into an illusionary world 30 feet above the ground on a platform connected to another by a thin walkway.

For many visitors to the Virtual Human Interaction Lab at Stanford University, one of their first experiences is “walking the plank.”

Jeremy Bailenson, the lab’s founding director, writes in his 2018 book “Experience on Demand: What Virtual Reality Is, How It Works, and What It Can Do” that some visitors gasp during these types of VR experiences. Others laugh, cry out in fear, throw out their hands to protect themselves, crawl on the ground or look around in wonder.

In one case, a federal judge dove in an attempt to save himself and catch an imaginary ledge after “falling off” the virtual platform. As a result, he slammed into a very real table – much to Bailenson’s horror.

“It was a scary moment, but he was just fine,” Bailenson said.

Thanks to its immersive capabilities, many organizations are making use of VR as a safety training tool. One major benefit is bringing trainees closer to real-world experiences without exposing them to real-world dangers.

However, as in the judge’s case, potential hazards exist, as do questions about where VR fits in the spectrum of safety training.

Why VR can work

In his book, Bailenson uses the terms “presence” or “psychological presence,” which he defines as “that peculiar sense of ‘being there’ unique to virtual reality.”

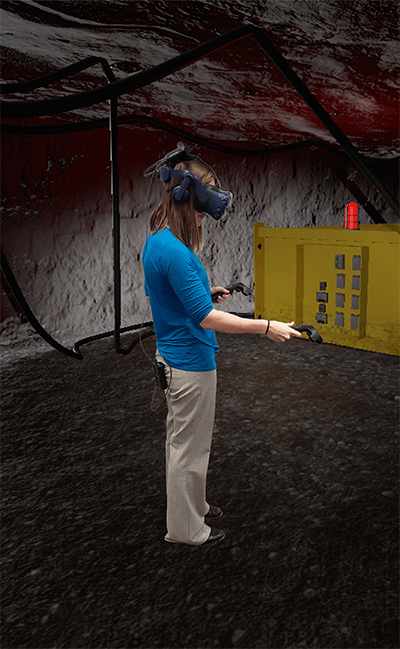

Biomedical Engineer Jennica Bellanca demonstrates virtual reality and simulation programs at NIOSH’s Pittsburgh Mining Research Division.

Presence occurs when the body’s “motor and perceptual systems” interact with a virtual world just as they would in the physical world.

“What makes VR different from using a computer is that you move your body naturally, as opposed to using a mouse and a keyboard. Hence, learners can leverage what psychologists call embodied cognition,” Bailenson writes.

This immersive experience can lead to better memory retention, according to the results of a 2018 study published in the journal Virtual Reality. Researchers from the University of Maryland asked participants to remember the locations of famous faces in two virtual locations: a room in a palace and a medieval town. The participants used a desktop computer and a VR head-mounted display while going through the exercises. When using the VR headset, the participants had a nearly 9% higher overall recall accuracy compared with using the computer.

Likewise, a 2016 study led by researchers from China involving high school students found that participants had better retention of knowledge – as well as improved test scores – when using VR-based learning.

On a more occupational note, a 2011 study from Iowa State University published in the Welding Journal found that welding students who used VR for at least half their training performed better “across four distinctive weld qualifications” than students who received only traditional training.

Over the past three years, the Houston Area Safety Council has used VR to train welders. The VR system provides data on the speed and spacing of welds and allows others in the classroom to see what participants are doing, providing them an opportunity to give feedback.

The reception to the training has been “quite positive,” said Dick Hannah, vice president of innovation and learning at the council.

“The trainees feel quite immersed in the environment and find the training worthwhile with VR experience,” he said.

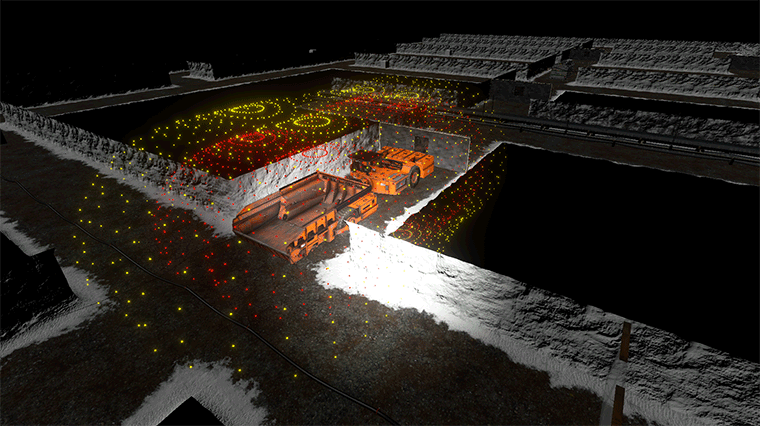

A NIOSH simulation depicts the potential safety concern posed by a haul truck’s blind spots. Hazards that may be clear from other perspectives can remain unseen by the operator.

Uses and benefits of VR

In addition to exposing workers to fewer real-world hazards during training, a key benefit of VR is greater efficiency, according to Justin Ganschow, business development manager for Caterpillar Safety Services, and Kim Shambrook, vice president of safety education, training and services at the National Safety Council. They shared two examples:

Training workers on how to repair or troubleshoot heavy equipment. Employers typically have to take a piece of machinery out of service so that it can be used for training, potentially interrupting work processes. “You can run several simulations in VR without taking a real bulldozer or truck out of your fleet at the cost of productivity,” Ganschow said.

Providing an interim step between the classroom and the real world. A newly trained crane operator isn’t quite skilled enough to operate the equipment safely. This shortcoming likely wouldn’t be discovered until the operator is on the worksite, potentially costing a day or more of work.

“You would have to take them off the job and put them back in the classroom, test them again, back and forth, back and forth,” Shambrook said. “If you have a VR application, you can test them first so you feel pretty confident that they get it before you’re putting them in that crane.”

Among other current uses of VR in safety training are hazard recognition, fall protection training and emergency situations. Hannah said the Houston Area Safety Council is looking to expand its VR training into subjects such as fire watch for hot work, confined spaces, scaffolding and hydrogen sulfide. Other examples of VR training programs:

The San Mateo County (CA) Fire Department uses an earthquake simulator – developed by VHIL – complete with a shaking floor and loudspeakers that put out a “thunderous rumble,” Bailenson writes in his book.

Caterpillar debuted its VR roadside safety training at the World of Asphalt trade show in February 2019, Ganschow said. Among the virtual hazards are backovers, oncoming traffic and debris from a concrete saw.

NIOSH is working on a handful of projects, including mine rescue and escape, said Jennica Bellanca, a biomedical engineer at the Pittsburgh Mining Research Division. The agency also is looking to enhance hazard recognition by using eye-tracking glasses.

Peter Simeonov, research safety engineer at NIOSH’s Protective Technology Branch in Morgantown, WV, said other projects include interactions with robots, and how drone use in construction might affect workers at height.

Virtual reality allows users to visualize invisible concepts. If a worker enters these areas, it will cause the vehicle to slow down (yellow) or stop (red). NIOSH screenshot.

Potential hazards and obstacles

So what are some of the potential drawbacks of adopting VR technology?

Physical hazards: Crashing into tables, walls and other objects are an obvious concern to keep in mind. Bailenson recommends prohibiting trainees from walking more than 30 feet in any direction – unless it’s “important and supported.”

‘Simulator sickness’: Visually induced motion sickness, also known as “simulator sickness,” stems from a disconnection between the eyes/brain and the body. While experiencing simulated movement, your eyes communicate to your brain that you’re in motion, although your body is not. Symptoms include nausea, sweating, dizziness, vomiting and fatigue, and may not appear immediately. In his book, Bailenson recalls how one VR user later collapsed after arriving home, falling into a fence post and hitting her head. She wasn’t seriously injured, he said.

To reduce the risk of simulator sickness, Bailenson recommends a “20-minute rule” for VR training: No more than 20 minutes in VR – “closer to five to 10 is better,” he said.

Bailenson’s other advice: Avoid abrupt shifts in users’ field of view (e.g., a simulated roller-coaster ride) during training, and buy a good pair of VR goggles.

Costs: Although the price of some VR headsets have dropped to hundreds of dollars per unit (some still could run in the five to six figures depending on how advanced they are), NIOSH experts caution that organizations need to factor in the development or purchase of training content in their VR costs.

“Development costs are significant for quality VR/AR training,” Bellanca wrote. “This can be deceptive because the development tools and head-mounted displays are relatively inexpensive.”

Implementation challenges: Successful implementation of VR, Bellanca said, requires “a multidisciplinary team to create impactful content,” such as programmers, graphic artists, user interface designers, subject matter experts and use case experts.

Ganschow recommends having several different end users participate in any beta testing to ensure training is usable by most people without issue. When developing safety content, the interaction between user and computer should be designed as simple as possible, he said.

Ergonomics issues: This is a concern worth considering, according to researchers from Northern Illinois and Oregon State universities, who found that when VR users extended their arms straight out during an exercise, some experienced discomfort in as little as three minutes. They also found that VR headsets can place stress on the cervical spine, potentially leading to a strained neck.

As a preventive measure, developers and programmers need to ensure participants or trainees interact with “objects” at eye level as often as possible, and those “objects” should be close to the body, study co-author Jay Kim, researcher at the OSU College of Public Health and Human Sciences, said in a Jan. 7 press release.

Generational differences: Reluctance among older workers to embrace new technology is another possible hurdle. Ganschow, however, said he was “surprised to see there is not generational differences in using VR. I’ve seen just as many seasoned employees use the system with ease as those that were born in the era of technology.”

Bailenson said one Walmart worker, a grandfather who was participating in VR training, said he couldn’t wait to tell his grandson that he used VR.

“When you put VR on, it’s not tech anymore,” Bailenson said. “You’re just having an experience. It’s not like there’s buttons (to push), you’re just doing what you normally do.”

VR’s role in safety training

Hannah is concerned that as the technology improves – and becomes more inexpensive – organizations may look to VR as a sole replacement for other kinds of training. This might prove a costly mistake, he said, because real-world situations have unforeseen variances that virtual training simulators may not take into account.

For example, Hannah talked about his time as director of training at HydroChemPSC from 2013 to 2017. As part of his role, he helped truck operators with advanced training on their vehicles. Many times, when the drivers went from the classroom to the field, the truck was different from the manual in some way.

“A training in virtual reality may have the employee put on a VR headset and go through a procedure or safety training on a certain type or style of truck,” Hannah said. “However, once he gets out in the field, he may be confronted with a different style of truck with different components. So now that person would be left with the choice of using a truck they aren’t familiar with, figuring it out on their own or just hoping for the best. That’s the concern.”

Because the long-term, or even short-term, effects of VR training on the human body and brain are still unknown, many experts say the technology is best used in shorter durations – as a way to augment or reinforce other kinds of training, such as classroom and hands-on experience.

A 2013 follow-up to the study on VR welder training by the same researchers from Iowa State found that VR was best used at low to medium difficulty levels of training. At the highest level, “it became apparent that the VR system was no longer sufficient and required supplementation from real-world training.”

Bellanca and Simeonov noted that VR is “not suited to solve every training need” and gave the example of learning how to put on a self-contained self-rescue device.

“VR does not let the user feel the device and components as they are deployed,” they said. “AR might be more appropriate and could provide informational overlays to enhance the experience.”

Hannah said the Houston Area Safety Council’s plans are for two- to three-minute VR exercises that reinforce the learning objectives of other types of training.

“Virtual reality has the added benefit of being an effective stopgap between our e-learning and our live hands-on learning,” Hannah said. “I believe in the long term, virtual reality will become the norm and VR headsets will be sent to offices to support training and career goals for workers. They can take VR training that helps increase their abilities, on demand, at the point of need and at their convenience across the nation.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)