A look at OSHA's Severe Violator Enforcement Program

SVEP turns 5 years old this summer. Is it working as intended?

Key points

- OSHA needs a program to focus its enforcement efforts on bad actors, stakeholders claim.

- One stakeholder objected to OSHA announcing that employers are in SVEP before the case has run its course.

- Nearly half of all SVEP-qualifying violations are contested, and nearly one-quarter of all employers originally identified as qualifying for SVEP are later removed.

OSHA has finite resources, and it would take decades for the agency to visit every employer in the country to ensure workers are being protected.

OSHA officials often have said that most employers are doing their best to keep workers safe. Yet employers who actively ignore safety regulations and put employees in danger are out there, and OSHA is charged with holding such “bad actors” accountable.

In an effort to better target its resources at non-compliant employers, OSHA chooses to focus on the most severe violators. To guide this focus, OSHA implemented the Severe Violator Enforcement Program.

Launched on June 18, 2010, SVEP is intended to target the worst of the worst violators. Employers in the program are placed on a public list identifying them as a severe violator, and they are subject to follow-up inspections.

Although OSHA said in a January 2013 self-review that the program was off to a “strong start,” some stakeholders have claimed that SVEP unfairly enrolls employers, or leaves out other employers who egregiously violate OSHA rules.

(Safety+Health contacted OSHA numerous times requesting a response to concerns raised by stakeholders and questions from S+H. At press time, the agency had been unable to arrange a response.)

Employers must meet at least one of the following criteria to be placed into the Severe Violator Enforcement Program:

- Any inspection in which an employer is cited with a willful, repeat or failure-to-abate for a serious violation related to an employee’s death or the hospitalizations of three or more employees

- Two or more willful, repeat, or failure-to-abates based on “high-gravity” serious violations related to a variety of high-emphasis hazards, such as falls, amputations or trenching

- Three or more willful, repeat, failure-to-abates based on high-gravity serious violations related to the potential release of a hazardous chemical, as defined in the Process Safety Management Standard

- All egregious – or per-instance citation – actions

Background

OSHA launched the Enhanced Enforcement Program under the President George W. Bush administration. Many stakeholders – as well as the Department of Labor Office of Inspector General – criticized EEP for not fully being able to identify and address severe violators. Among the criticisms: too many employers were enrolled in the program and OSHA lacked follow-up inspections.

SVEP was intended to change that. The program has more stringent requirements than EEP, and OSHA has been able to conduct most of its follow-up inspections under SVEP, according to the agency’s 2013 white paper on the program.

“The program has succeeded in guiding OSHA enforcement toward recalcitrant employers by targeting high-emphasis hazards, facilitating inspections across multiple worksites of employers found to be recalcitrant, and by providing regional and State Plan offices with a nationwide referral procedure,” the agency said.

‘Unproven allegations’?

OSHA’s most recent SVEP case log – published Oct. 1 – lists 434 employers in the program. The log provides employers’ names and addresses, as well as dates of when the case was opened and citations were issued. Also included for each employer is an SVEP log number, running chronologically for every new employer.

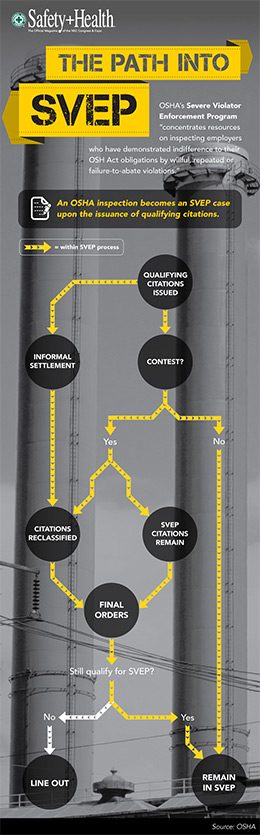

This image is available as an infographic that you can embed on your website or blog.

However, 152 of the log numbers are missing. This suggests that as many as 152 employers – or nearly one-quarter of the total number of SVEP employers – entered into the program but did not remain. Because no employer has formally been removed from the program, according to various reports, these 152 employers could have gone through a process known as “lining out.”

Employers are formally removed from the program only when they meet certain criteria of good behavior. (See “SVEP removal”) Lining out occurs when the SVEP-qualifying citations originally issued to an employer are later withdrawn through settlements or overturned through a court ruling. OSHA does not consider lining out the same as being formally removed from the program, and, as the agency describes in its white paper, lining out indicates the employer never should have qualified for SVEP in the first place.

“The issue is employers are qualified into the SVEP at the time citations are issued. The citations are nothing more than allegations, unproven allegations,” said Eric Conn, a founding partner of the Washington-based law firm Conn Maciel Carey.

For Conn, this is an inherent problem with SVEP: Because the SVEP list is public and OSHA issues press releases announcing some employers being entered into the program, employers may be labeled as severe violators before they have had an opportunity to contest or settle the citations.

Midsouth Steel has experienced this. In November 2011, OSHA issued a press release announcing three willful citations for fall hazards against the Atlanta-based roofing contractor. The press release also said Midsouth Steel was placed into SVEP.

In early 2012, the company brought George Henry on board as its safety director and tasked him with ensuring total compliance with OSHA regulations. As part of a settlement agreement with OSHA, the original citations were reduced and Midsouth Steel no longer qualified to be in SVEP. As a result, the company lined out.

Although the ramifications of the original violations and being temporarily placed into SVEP are minimal for Midsouth Steel today, Henry is concerned about OSHA announcing such allegations. As of press time, the press release detailing the original violations against Midsouth Steel and its placement in SVEP was still on OSHA’s website.

“When you’re on that list, it opens you and the general contractor’s project up to more scrutiny than normal,” Henry said. “Anytime you indict somebody and then declare them guilty, and then change the outcome of that and do not make that public, that’s not a good thing.”

Conn alleges that enrolling employers into SVEP before their case is fully adjudicated violates the law and the employer’s right to due process, as guaranteed under the Constitution. The process to contest OSHA citations – which is an employer’s right – may take years.

Further complicating matters is the three-year time period employers must remain in SVEP if they do not line out. The time period does not begin until the case is officially disposed, so if an employer chooses to fight the SVEP-qualifying citations and loses, it must spend three years in SVEP plus the amount of time it took for the case to go through the judicial process.

According to OSHA’s white paper, 44 percent of SVEP cases were contested. The national contest rate – which includes other-than-serious violations – was 8 percent in 2010 and 2011.

Too narrow?

According to Celeste Monforton, the percentage of contested SVEP cases is not unexpected. The stakes are high for employers that qualify for the program, giving them more incentive to contest the violations, said Monforton, who is a professional lecturer at the George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services.

Unlike Conn, however, Monforton believes the program should be broadened. The number of employers enrolled in SVEP is relatively small considering the number of employers in the country, and the criteria for entering the program are almost overly stringent, she said.

For example, an employer needs three willful or repeat violations of the Process Safety Management Standard to qualify for SVEP – a criterion Monforton claims is too narrow given recent industrial disasters.

“One violation could have a catastrophic result,” she said.

Likewise, she has concerns about how employers can line out of the program. When violations are reduced, either through settlement or the courts, the employer might leave SVEP with no public record being kept.

Comparing it to a bank robber convicted of robbing several banks but acquitted of robbing one, Monforton said the idea behind SVEP is defeated when an employer is able to be removed from the program after one violation out of several is reclassified.

Regarding OSHA announcing in press releases that certain employers have been designated as severe violators, Monforton said the agency has some latitude.

“The agency has the authority to set up criteria on how it wants to use its resources,” she said. “There are always going to be employers who object to any label. But OSHA is just doing its job.”

Improvements and SVEP’s future

Both Conn and Monforton say OSHA could improve how it does its job by making some changes to ensure SVEP targets truly severe violators.

Conn suggested that OSHA place an employer in SVEP only after a final order is given. This would prevent employers being placed into the program and then lining out.

“Just wait until you’ve actually proven that employer is a bad actor,” he said. Additionally, he recommends that OSHA “start the clock” on the three-year time period to exit the program whenever the employer enters SVEP, not simply when the case is adjudicated.

Conn objected to OSHA keeping an employer in SVEP based on any serious – not necessarily a willful or repeat – violation found in subsequent inspections, noting that it takes a willful or repeat violation to qualify into the program. This makes the threshold for keeping employers in the program too low, he said.

Both Conn and Monforton recommend that OSHA re-examine the high-hazard activities that can place employers into the program. Conn advocated removing grain handling, as OSHA’s recent, active targeting in the industry has led to improved outcomes, including fewer deaths. However, Monforton stressed the need to add hazards, specifically asbestos. Noting that OSHA has an asbestos standard on the books, and the fiber has been a known hazard for decades, she said any violation of those rules should place employers in SVEP.

Monforton said more transparency for the program would be beneficial, including OSHA’s own assessment of the program and regular updates on the number of follow-ups conducted and removals.

But no matter what changes may be made to the program, or if it is replaced during another presidential administration, OSHA will always need a mechanism to focus its enforcement on bad actors.

“OSHA is a small-budget agency, and they’re stretched pretty thin,” Conn said. “Some sort of program that is thoughtfully conceived and consistent with the constitution and the laws of the land is a good idea.”

SVEP removal

Employers placed into the Severe Violator Enforcement Program do not remain there forever. In August 2012, OSHA issued a memorandum providing guidance to inspectors on how to remove employers from the program. First, employers must remain in SVEP for three years after the final disposition of their case. This could include a settlement agreement or court of appeals decision upholding some of the original citations.

To be removed from the program, employers must:

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)