Home sweet hazard

Home health care workers face multiple risks with little oversight

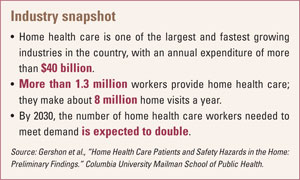

By Ashley Johnson, associate editorEven though home health care is one of the fastest-growing industries in the United States, experts say efforts to protect workers are lacking.

Nurses, aides and other clinicians who provide care in patients’ homes can encounter not only risks associated with health care, such as exposure to bloodborne pathogens, but also household hazards ranging from clutter to verbal and physical abuse. “They have almost like a dual set of potential occupational hazards, yet they’ve been tremendously understudied,” said Robyn Gershon, associate dean of research resources and professor in the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University in New York.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the home health care industry employs more than 1 million workers, the bulk of whom are home health aides and personal and home care aides, along with more than 125,000 registered nurses. The work can be both physically and emotionally demanding, with aides often receiving low wages and few, if any, benefits.

Research shows home health care workers can be exposed to household hazards such as unsanitary surroundings; conditions conducive to slips, trips and falls; cigarette smoke; and vermin and aggressive pets. Some also receive threats of violence from the patient, family members or neighbors. Preliminary results from a NIOSH study on the risk of work-related violence for home health care workers show 4.6 percent of 677 respondents reported having been assaulted by a patient at least once in a 12-month period. That has huge implications for worker safety. A study led by Gershon and published last year in the American Journal of Infection Control (Vol. 37, No. 7) found nurses exposed to violence in their patients’ homes were nearly 3.5 times more likely to report needlestick injuries. Likewise, nurses reporting household stressors were almost twice as likely to experience needlesticks.

Lack of support

Gershon noted home health care workers lack access to the support typically present in a traditional health care setting – an infection control officer, safety director and security officer. Unlike their hospital counterparts, home workers cannot simply go to their own emergency room for care. They also might not have anyone to leave their patient with.

Under OSHA regulations for bloodborne pathogens, home health care employers are responsible for hepatitis B vaccinations, post-exposure evaluation and follow-up, recordkeeping, generic training requirements, and providing personal protective equipment to employees. But OSHA cannot cite employers for site-specific violations, such as maintaining a clean and sanitary worksite, handling regulated waste, and ensuring use of PPE and engineering controls. An OSHA spokesperson said any enforcement activities would occur at a home health care agency.

“There’s a gap there,” said Margaret Quinn, occupational hygienist and professor in the School of Health and Environment at the University of Massachusetts in Lowell. “OSHA can’t, for example, hold an agency responsible if somebody in the home is using sharps in a manner that’s not consistent with the bloodborne pathogens standard.”

She said the fact that the workplace is a private home can make it difficult to implement effective safety interventions. Patients and family members often fail to prepare their home adequately and may practice unsafe habits, such as reusing their sharps or leaving them around the house, she said.

In a study conducted by Quinn and published last year in the American Journal of Public Health (Vol. 99, No. S3), home health care workers identified several contributing factors to sharps injuries, including lack of work space, poor lighting, difficulty lifting patients and time pressures. Although OSHA requires the use of safe needle devices, almost 40 percent of nurses in the study reported using sharps without safety features. Underreporting of sharps injuries also was identified as a problem.

Along with needlesticks and other sharps injuries, workers are at risk for musculoskeletal injuries from lifting patients. “The home care worker is often alone in her caregiving setting, so if something happens she can’t call other team members in the hospital to help her. It’s the isolated conditions that can also enhance the ergonomic issues,” Quinn said. “We have to get creative about how we’re going to improve occupational health and safety in a home setting,” she said. “What OSHA might be able to do is help agencies do better education of their clients.”

In addition to funding studies such as the ones performed by Gershon and Quinn, NIOSH is developing tools to educate home health care workers. In January, NIOSH published a hazard booklet that includes checklists for employers and workers. Other tools in the works include a project in California focused on educational products for low-literacy workers and “fast fact” cards containing hazard information, according to Teri Palermo, registered nurse and coordinator for the health care and social assistance sector of the National Occupational Research Agenda at NIOSH.

“This is a big concern with the nation because of the aging population,” Palermo said, “and we know that a lot of people are going to be requiring home health care, so it’s certainly an issue that’s on our radar.”

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)